Rosemary Mayer: Ways of Attaching

Sep 09 2021 - Jan 09 2022

Download Press Release

Download Checklist

Ways of Attaching is the first institutional survey exhibition of American artist Rosemary Mayer (1943-2014). The exhibition provides an overview of the artist’s work, moving from early conceptual experiments of the late 1960s through to textile sculptures and drawings made in the early 1970s, before focusing on propositional and durational performances and temporary monuments made from 1977-1982. Highlighting Mayer’s formal interest in draping, knotting and tethering, the exhibition focuses on the artist’s process of constructing real and imagined networks and constellations, in which friends and historical figures feature in expressions of affinity and attachment.

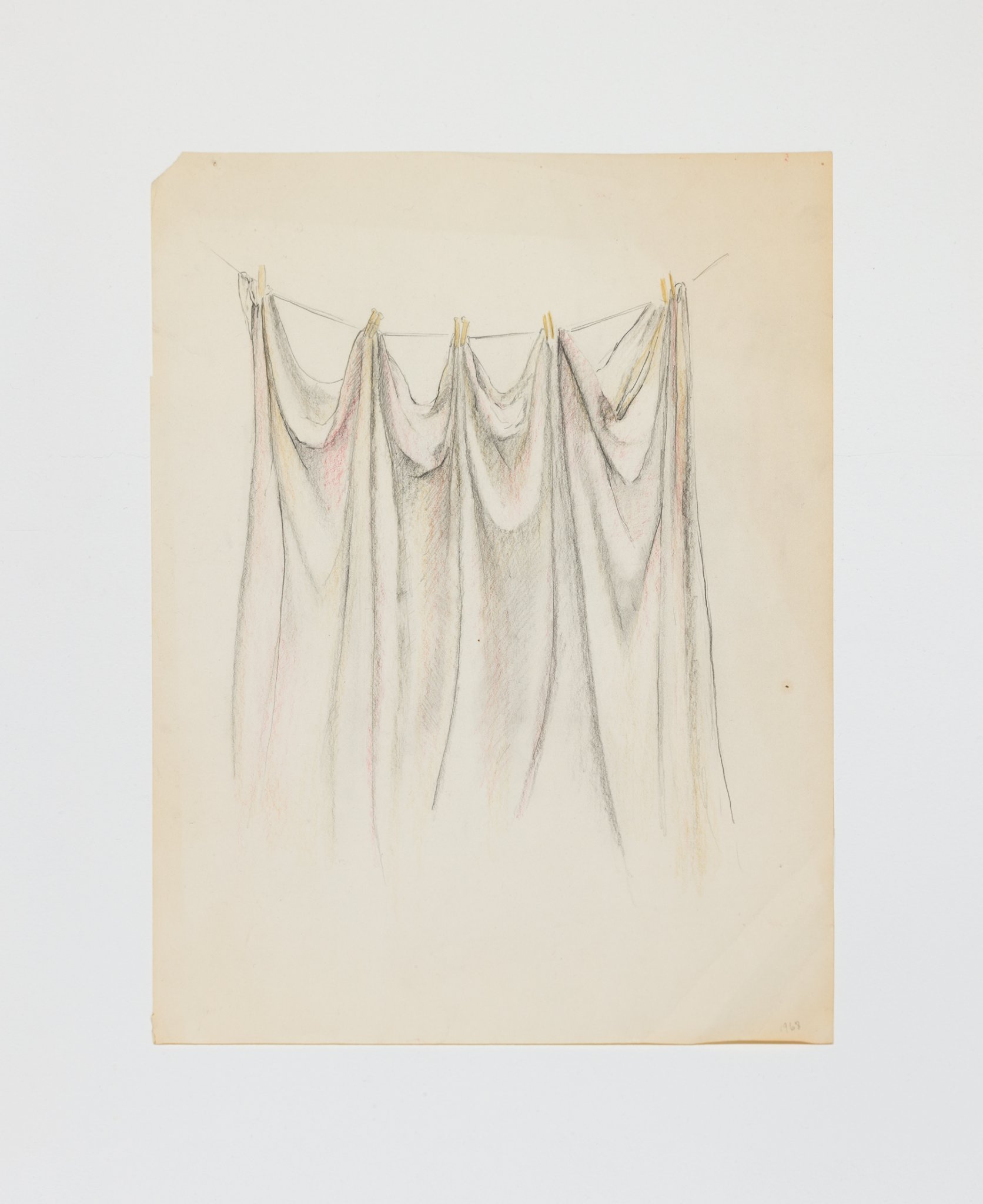

Mayer was born in Brooklyn, NY, and lived in New York City all her life. The earliest works included in the exhibition explore rule- and process-based systems, as well as record-keeping of small everyday occurrences, and were made in the late 1960s in an atmosphere of ferment surrounding conceptual art. Included are several contributions to the journal 0 To 9 (1967-9), edited by her sister, the poet Bernadette Mayer, and her then-husband, the artist Vito Acconci, as well as drawings of garments, and laundry drying on a line.

In 1971, Mayer began creating wall-based works by layering multiple fabrics, as well as working on drawings of “impossible” fabric sculptures that were connected by multitudes of knots and loops. That same year, she began taking part in a small consciousness-raising group and started incorporating feminist gestures into her work, including naming her sculptures after historical female figures and employing materials and motifs that were traditionally considered feminine. In 1972, she became one of the founders of A.I.R., the women’s cooperative gallery in New York, and had a solo exhibition there in 1973, producing large textile sculptures in which layers of fabric were hung from scaffolds and frames. The exhibition at SI marks the first time that Galla Placidia (1973), named after a 5th century Roman Empress, has been shown in the US since. As the critic Lawrence Alloway wrote of this work in Artforum in 1976: “the feminine figure is absent as well as present, missing as well as given.” Several drawings in the exhibition, made after a research trip to Europe in 1975, highlight this preoccupation, depicting garments worn by invisible bodies that were inspired by figures from Baroque and Mannerist painting, or petals and leaves dissolving into formlessness.

On the second floor of SI are drawings, photographs and documentation relating to Mayer’s durational sculptures from 1977-82, which she referred to as “temporary monuments,” made from materials such as weather balloons, ribbons and snow. In each of these works, drawings act to propose, publicize, document and celebrate events, or even to render on paper fantasy projects that would never be realized. These works employed a unique lexicon developed by the artist to connect sites to time, drawing together the grounded and the cosmic. On each balloon that she floated above a rural landscape for Some Days in April (1978), Mayer painted the name of a celebrant with a date, a constellation overhead at that moment and a flower currently in season. For Snow People (1979) in Lenox, Massachusetts, she sculpted a number of snow figures and dedicated them, plurally, to the former inhabitants of the town who shared a name: all of the “Carolines” and all of the “Fannys,” who were given fleeting form before melting away to nothing. Each of these works functions as a counterproposal to the heavy permanence that prevailed in the art and monuments of the time, instead emphasizing the passing of time and the shifting seasons.

Rosemary Mayer: Ways of Attaching is organized in partnership with Ludwig Forum, Aachen; Lenbachhaus, Munich; and Spike Island, Bristol, where the exhibition will travel in 2022. The exhibition is organized in collaboration with Marie and Max Warsh of the Estate of Rosemary Mayer.

This exhibition is made possible through support from the Terra Foundation for American Art. Additional support is provided by the Robert Lehman Foundation; ChertLüdde, Berlin and Gordon Robichaux, New York.

SI wishes to thank the lenders to the exhibition: Amherst College Archives & Special Collections; ChertLüdde, Berlin; the Estate of Rosemary Mayer; Peggy DeCoursey; Gordon Robichaux, New York; Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University; Lenbachhaus, Munich; Patricia Martin; Bernadette Mayer; Ales Ortuzar; David Platzker/Specific Object; Beth Rudin DeWoody; Ugly Duckling Presse; the interview participants: Jacki Apple, Donna Dennis, Harmony Hammond, Bernadette Mayer, Grace Murphy, Adrian Piper, Marie Warsh, Max Warsh and Martha Wilson; and design consultants, New Affiliates. The Estate of Rosemary Mayer wishes to thank Jennifer Chert, Amanda Friedman, Florian Lüdde, Gary McGowan, Jacob Robichaux, Gillian Sneed, Clarissa Tempestini and James Walsh for their help preparing this exhibition. For ongoing support and encouragement, the Estate thanks family and friends of Rosemary Mayer: Peggy DeCoursey, Donna Dennis, Alyssa Gorelick, Philip Good, Katt Lissard, Bernadette Mayer, Lewis Warsh, Sophia Warsh, Veera Warsh and Zola Warsh. The Estate is also grateful to Clarie Barliant, Sonel Breslav, April Childers, Ashton Cooper, Bridget Donahue, Samantha Friedman, Katie Geha, Janice Guy, Miciah Hussey, Julia Klein, Nick Mauss, Heidi Norton, Noam Parnass, Maika Pollack, Vlad Smolkin, Ricardo Valentim and Wendy Vogel for their support of Rosemary Mayer’s work.

On the occasion of the exhibition, two books will be published: a catalogue of the exhibition, featuring new essays and scholarly contributions to Mayer’s practice planned for publication in May 2022, and a book of correspondence between Mayer and her sister, Bernadette Mayer, published in December 2021.

This exhibition is organized by Laura McLean-Ferris, Chief Curator, with Alison Coplan, Curator, Swiss Institute.

About Rosemary Mayer

Rosemary Mayer (1943-2014) was a prolific artist involved in the New York art scene beginning in the late 1960s. Best known for her large-scale sculptures using fabric as the primary material, she also created works on paper, artist books and outdoor installations exploring themes of temporality, history and biography. She was additionally a writer, art critic and translator. Mayer was a founding member of A.I.R. Gallery, the first cooperative gallery for women in the U.S. and had one of the earliest shows there. During the 1970s and 1980s, her work was also shown at many New York alternative art spaces, including The Clocktower, Sculpture Center and Franklin Furnace, and in university galleries throughout the country. In 1982, her translation of the diary of Mannerist artist Jacopo da Pontormo was published along with a catalogue of her work. Recent exhibitions of Mayer’s work have taken place at Southfirst, Brooklyn (2016), Lamar Dodd School of Art at the University of Georgia (2017), ChertLüdde, Berlin (2020) and Gordon Robichaux, New York (2021). Her work was included in the exhibition Bizarre Silks, Private Imaginings and Narrative Facts, etc., curated by Nick Mauss at Kunsthalle Basel (2020).

Image: Rosemary Mayer, Untitled (8.26.71), 1971, Colored pencil and colored marker on paper, 14 x 11 inches.

Related Events

Press

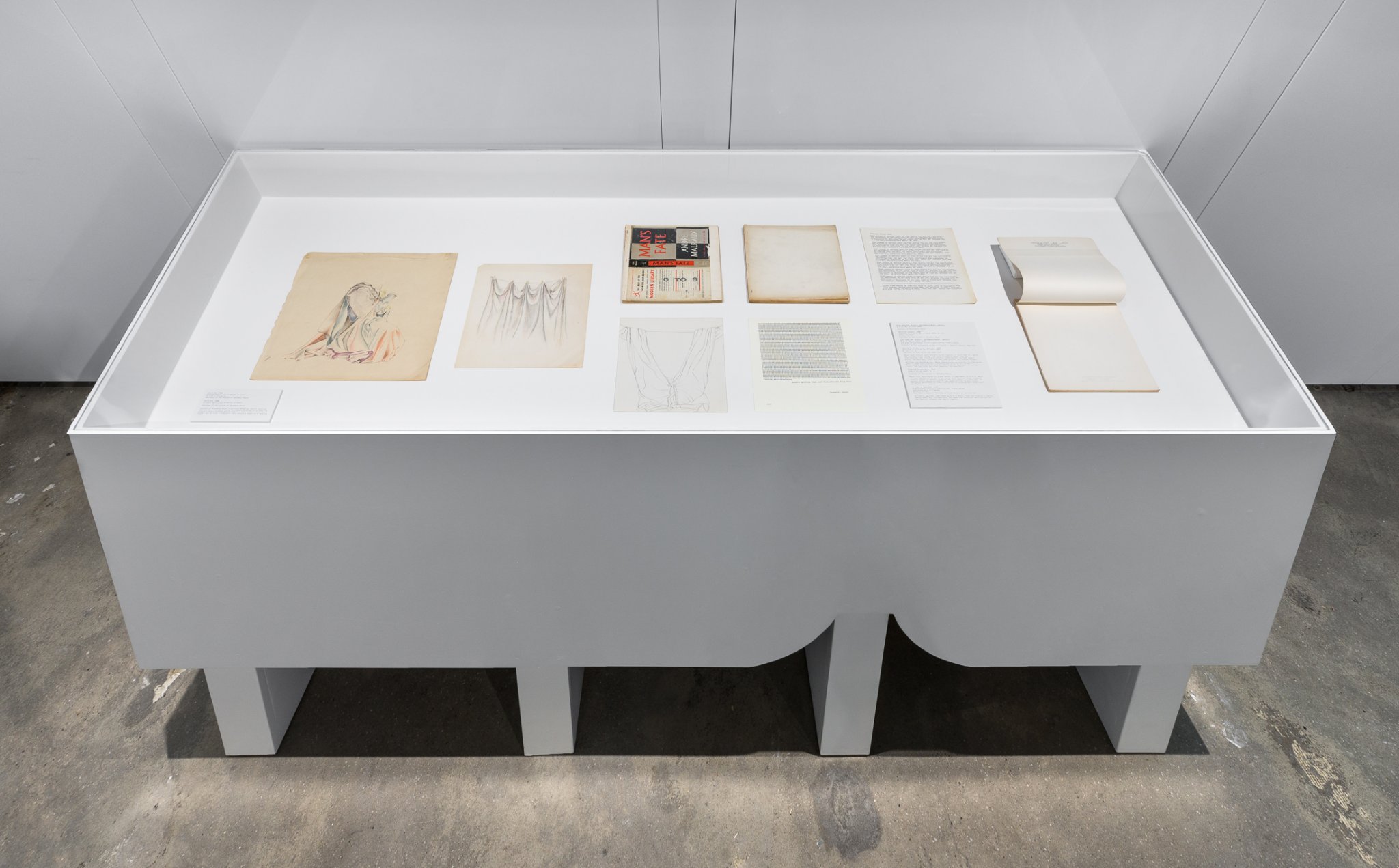

Rosemary Mayer: Ways of Attaching, installation view.

Rosemary Mayer: Ways of Attaching, installation view.

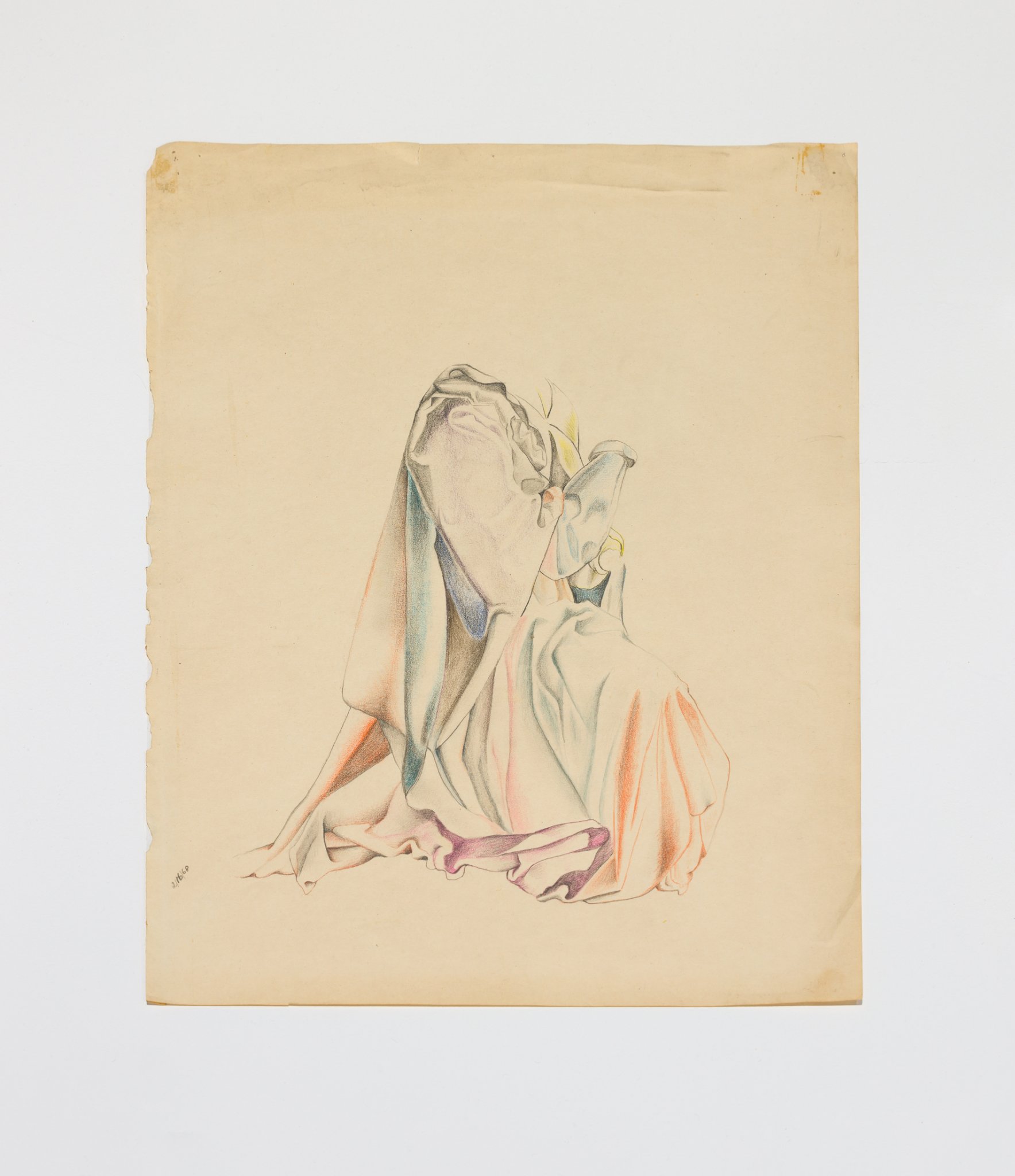

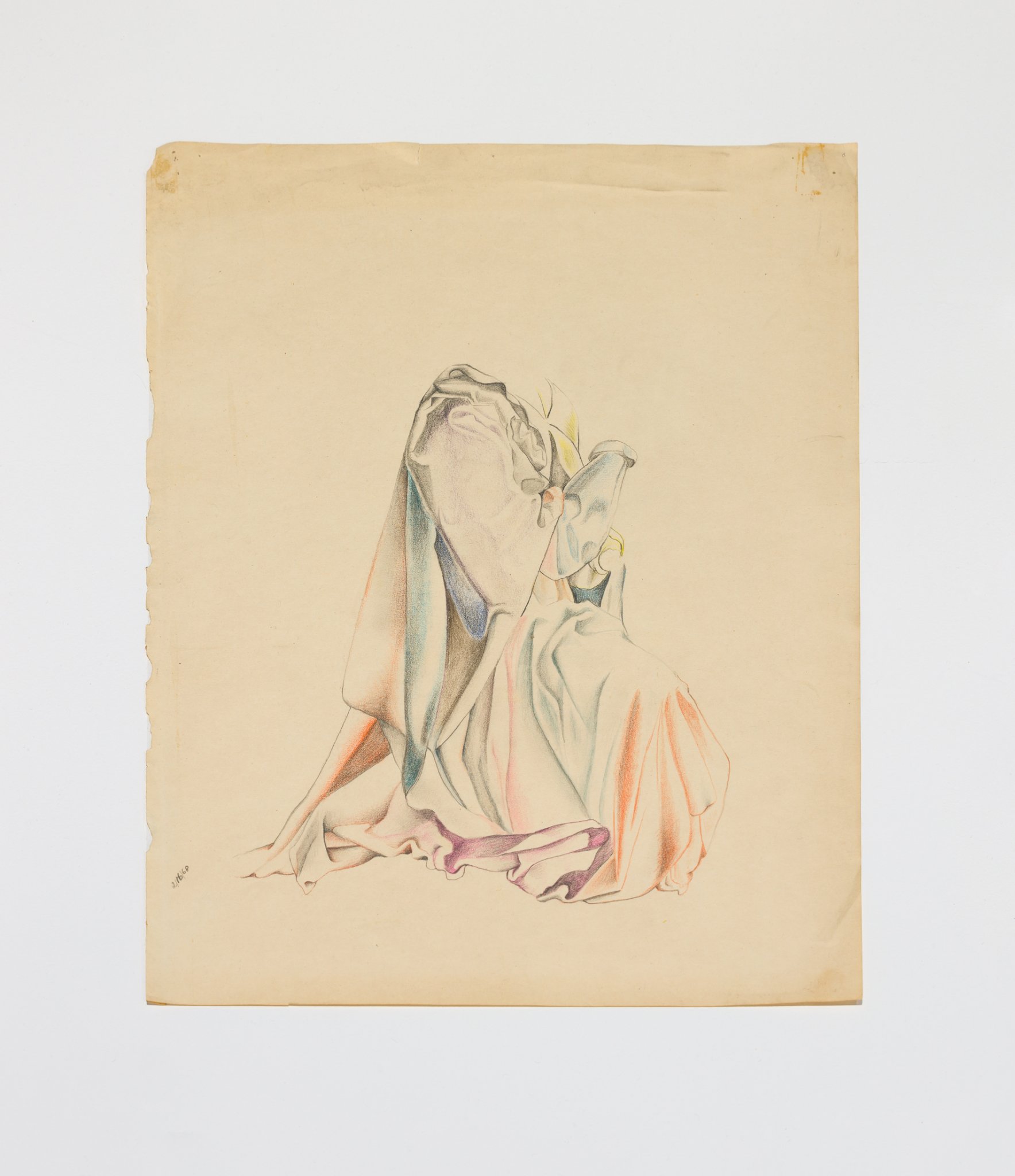

Untitled, 1968. Colored pencil and graphite on paper. 16 5/8 x 13 3/4 in. Courtesy of the estate of Rosemary Mayer.

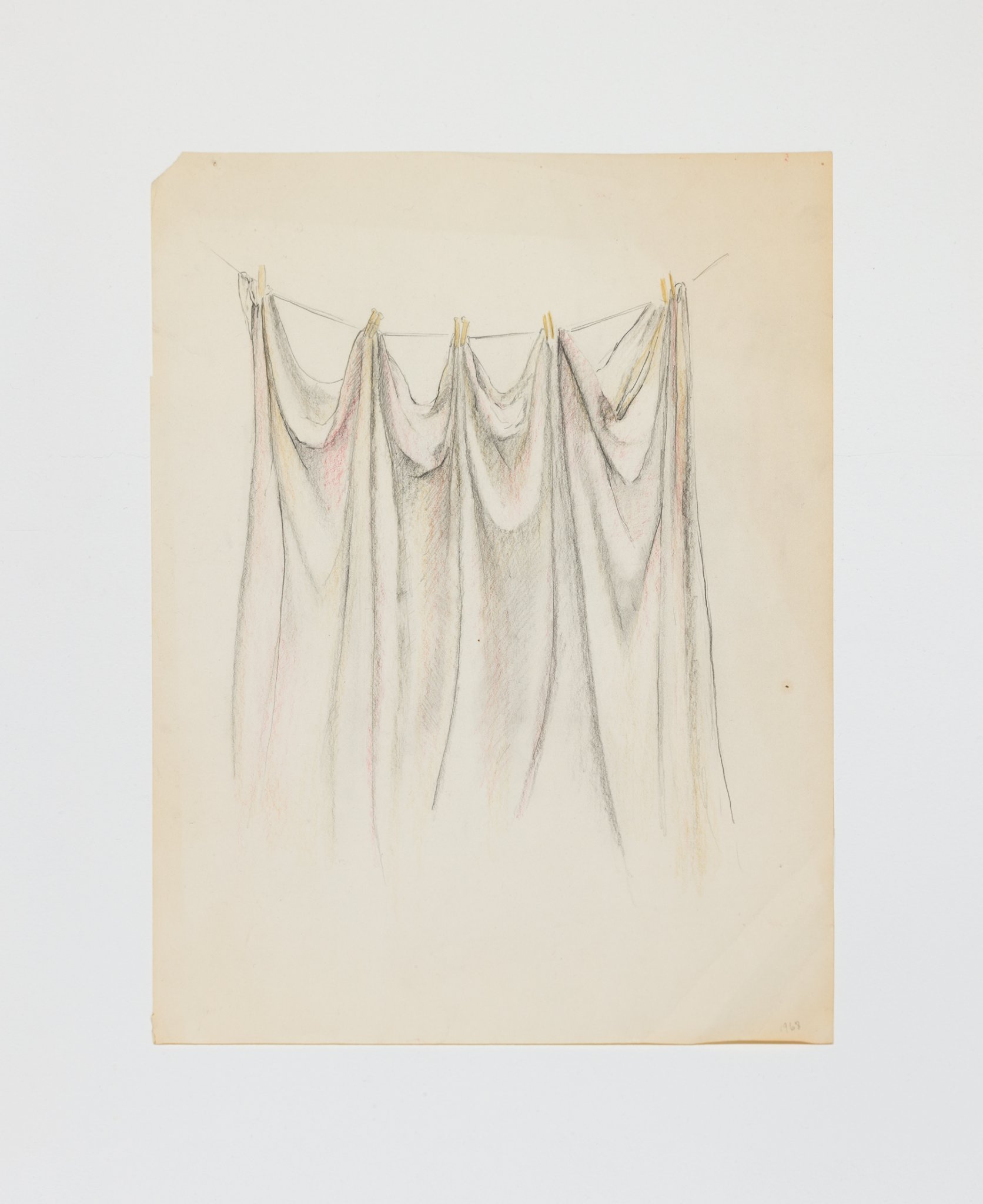

Untitled, 1968. Colored pencil and graphite on paper. 13 1/2 x 10 1/4 in. Courtesy of the estate of Rosemary Mayer.

Several of Rosemary Mayer’s earliest drawings depict textiles and fabrics, including these

sketchbook drawings of a kneeling figure’s dress folding gently around a body without head or

hands, and of five clothespins that attach a sheet to a washing line.

Untitled Satin & Paint, 1970. Acrylic paint on satin and string. 48 x 72 in. Courtesy of the estate of Rosemary Mayer and ChertLüdde, Berlin.

Mayer was making rule-based paintings in the late 1960s that alternated blocks of color and

shape, but in 1968, she began making artworks that emphasized the material qualities of

canvas as a fabric. She began pulling raw canvases away from their stretchers to let them

hang loosely before abandoning the stretchers and tacking the canvas and other fabrics

directly to the wall: twisting, threading, staining and painting them, as in Untitled Satin

and Paint. This is the only surviving work of this type.

Galla Placidia, 1973. Satin, rayon, nylon, cheesecloth, nylon netting, ribbon, dyes, wood, acrylic paint. 108 x 120 x 60 in. Courtesy of the estate of Rosemary Mayer and ChertLüdde, Berlin.

In 1972, Mayer became one of co-founders of A.I.R. Gallery, the women’s cooperative gallery,

together with nineteen other women, including Judith Bernstein, Agnes Denes, Harmony Hammond, Howardena Pindell, and Nancy Spero. In 1973, for her solo exhibition there, Mayer exhibited three large textile sculptures named after historical female figures:

Hiroswitha,

The Catherines (named for a multitude of women) and

Galla Placidia, named after a 5th Century Roman Empress who led during the chaotic final period of the Roman Empire, as regent for her son. This naming system was a deliberate feminist gesture by Mayer, which, she wrote, was an “attempt to connect the works with women in history, not sculpture as picture of, but as hint to, reminder of, groups of characteristics.”

Galla Placidia, 1973, detail.

Rosemary Mayer: Ways of Attaching, installation view.

Balancing, 1972. Rayon, cheesecloth, cord, acrylic rods. 126 x 108 1/4 x 3 7/8 in. Courtesy of the estate of Rosemary Mayer and ChertLüdde, Berlin.

Balancing employs a hanging system of rods and cords to support two sections of draped fabric, connected by a length of dyed cheesecloth that passes between them. The sculpture possibly relates to the drawing

Abracadabra Sailboat (1972), on the wall nearby, and the use of cords to create lines that describe and frame the fabric suggests some relationship with

the act of drawing.

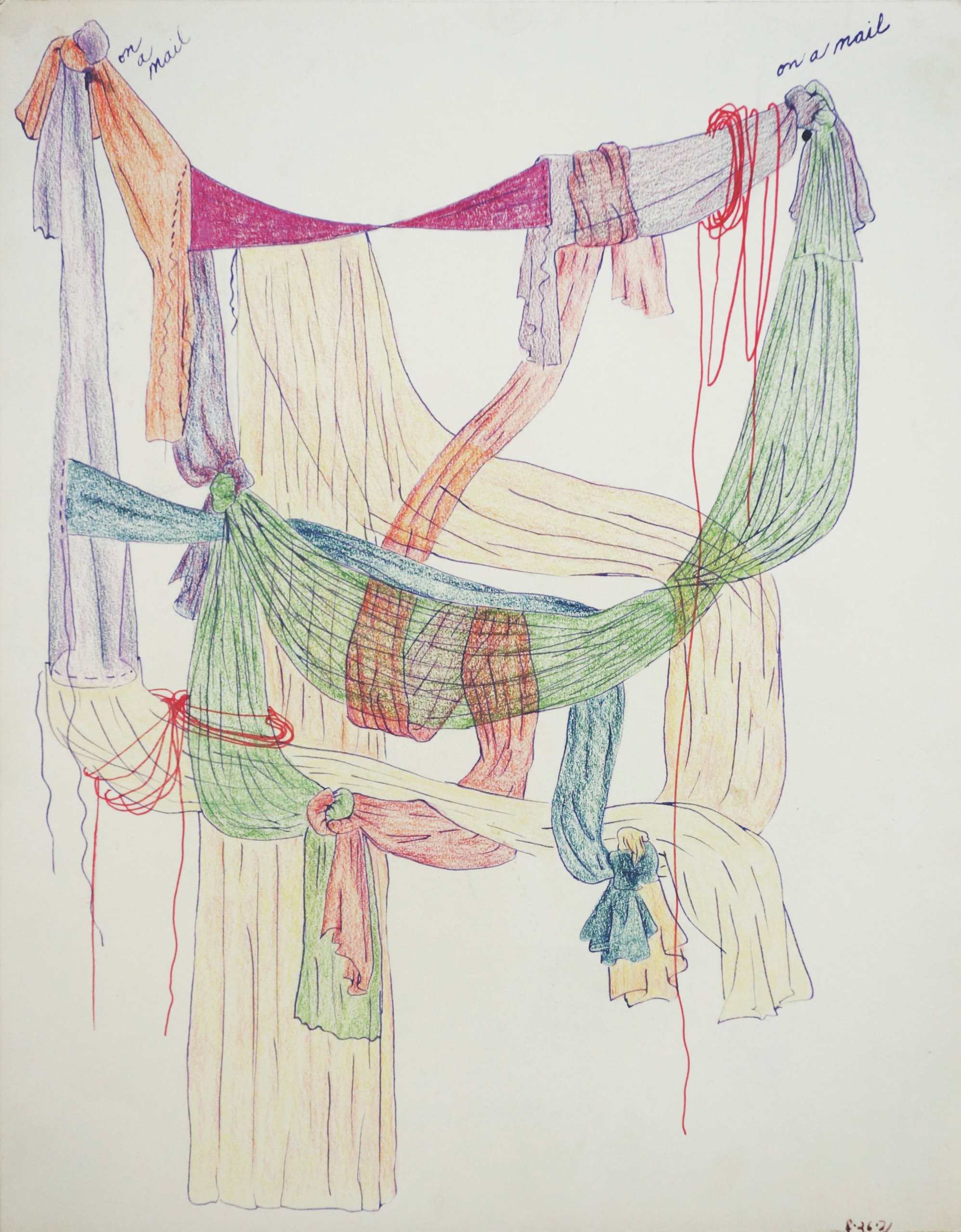

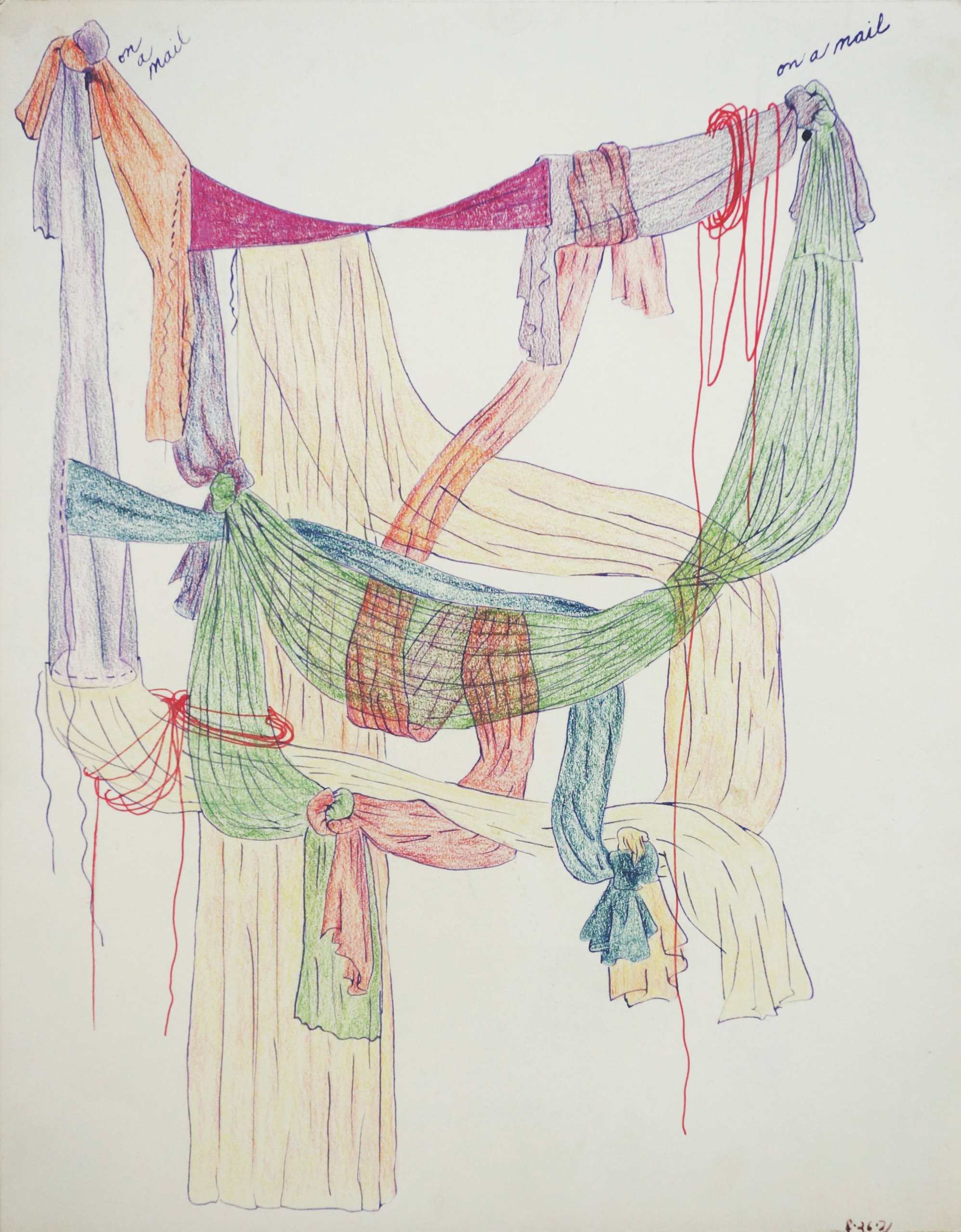

From left:

Untitled (8.25.71), 1971. Colored pencil and colored marker on paper. 14 x 11 in.

Untitled (8.26.71), 1971. Colored pencil and colored marker on paper. 14 x 11 in.

Untitled (8.27.71), 1971. Colored pencil and colored marker on paper. 14 x 11 in.

Untitled (8.27.71), 1971. Colored pencil and colored marker on paper. 14 x 11 in.

All courtesy of the estate of Rosemary Mayer and ChertLüdde, Berlin.

In 1971, Mayer began to make drawings of imaginary fabric constructions that she described as “impossible” pieces. She wrote in her journal that this method of drawing allowed her to play

with “colors and all the possibilities of draping, tying, sewing etc. without $ and… unfettered by space and size.” In addition to being a means through which to explore sculptural freedom, Mayer employed drawing as proposition, documentation, notation, and as a way of further examining aspects of sculptures that she did produce.

From left: Untitled, 1972. Colored pencil and graphite on paper. 14 x 17 in. De Medici, 1972. Colored pencil and graphite on paper. 17 × 14 in. Hypatia, 1972

Colored pencil and graphite on paper. 17 x 14 in.

All courtesy of the estate of Rosemary Mayer and ChertLüdde, Berlin.

Clockwise from top:

Study for Hroswitha, 1972. Colored pencil and graphite on paper. 8 1/2 x 11 in. Courtesy of the estate of Rosemary Mayer and ChertLüdde, Berlin.

Abracadabra Sailboat, 1972. Colored pencil and graphite on paper. 11 x 14 in. Courtesy of the estate of Rosemary Mayer and ChertLüdde, Berlin.

Net Section, 1972. Colored pencil and graphite on paper. 14 x 17 in. Courtesy of Patricia Martin.

These drawings were made at different stages of Mayer’s sculptural process. Net Section

(1972), De Medici (1972) and Hypatia (1972) are textile sculptures that no longer exist,

though photographic documentation suggests that the drawings were made after the sculptures

as forms of documentation.

Study for Hroswitha refers to Hroswitha (1973), one of three large textile sculptures

included in Mayer’s solo exhibition at A.I.R.. Mayer writes that the sculpture was named

after “a German Latin poet of Gandersheim in Saxony. The nuns of Hroswitha’s convent

performed her plays for the court of Theophano (of Byzantium) and Otto I, c. 980.”

From left:

Untitled, 1972. Colored pencil and graphite on paper. 15 x 20 in. Courtesy of the estate of Rosemary Mayer.

Untitled, 1972. Colored pencil and graphite on paper. 14 x 17 in. Courtesy of the estate of Rosemary Mayer and ChertLüdde, Berlin

Untitled, 1972. Colored pencil and graphite on paper. 12 x 9 in. Courtesy of the estate of Rosemary Mayer and ChertLüdde, Berlin.

During the mid-1970s, Mayer referred often to the work of painters Matthias Grünewald (c.1470-1528) and Jacopo Pontormo (1494-1557), as well as other Italian Mannerist painters, an

interest that grew following a trip to Europe in 1975. In 1976, she began working on a

translation of Pontormo’s diary, exploring the intersection between this artist and her own

work, which was published in 1982 as

Pontormo’s Diary. [A copy is on view in SI’s Reading Room on the second floor.]

Mayer created a series of drawings based on the way that garments carry the gestures of their

wearers.

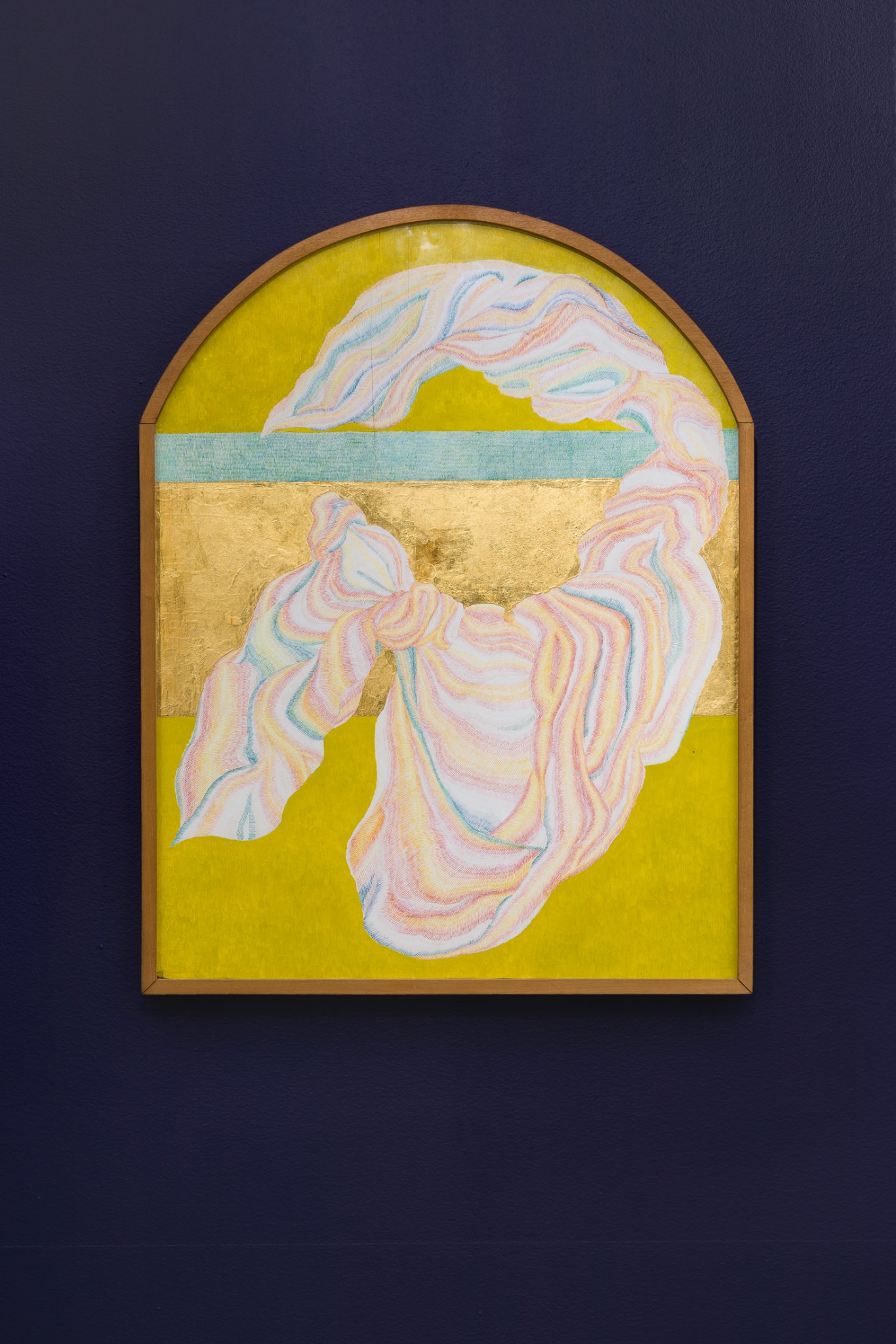

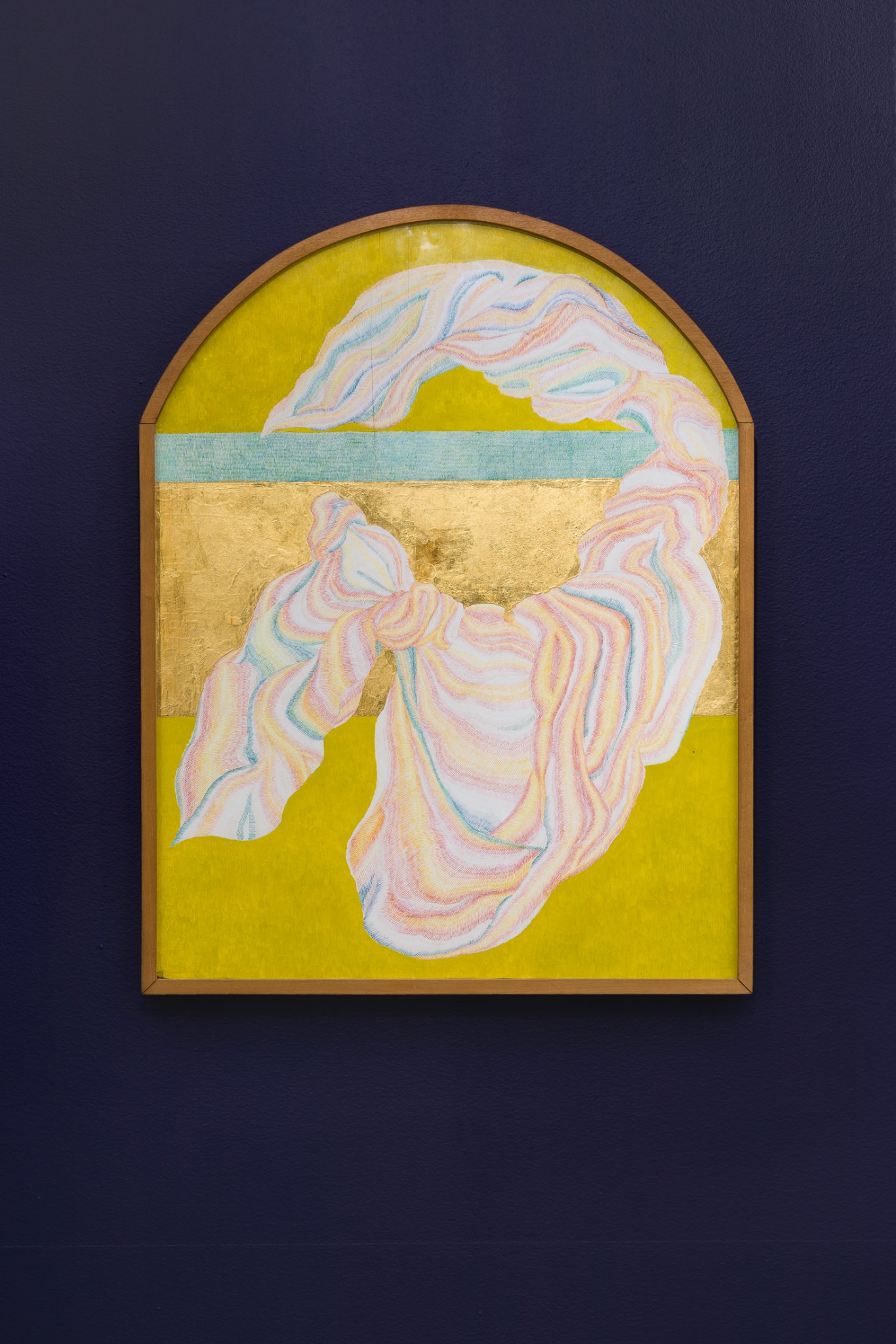

Fifth Angel Sleeve takes formal cues from the sleeve of the Annunciation Angel featured in the

Isenheim Altarpiece painted by Grünewald c. 1510. In a 1975 essay, she wrote of angels: “Barely visible, elusive and transparent, their motions caught in folds and layers of floating cloth. Angel sleeves, markers, records of their gestures, their presence.”

Rosemary Mayer: Ways of Attaching, installation view.

Hypsipyle, 1973. Satin, rayon, nylon, cheesecloth, nylon netting, ribbon, dyes, wood, acrylic paint. 48 x 108 x 6 in. Courtesy of Lenbachhaus, Munich.

Hypsipyle was Mayer’s final work made by draping fabric on a sculptural scaffold. It was named after a mythological queen of Lemnos in Ancient Greece, who refused to kill her father during a great war between men and women and had to flee as a result. Mayer wrote that the sculpture “dealt with corners – how to get a sculpture out of a corner, how to go across a

corner.”

On pedestal:

Crescentia, 1975. Wire screen, copper wire, synthetic mesh, paint. 13 1/2 x 19 3/4 x 13 1/2 in. Courtesy of the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University Gift of the artist, made possible through the Creative Artists Public Service Program.

Crescentia is one of a series of sculptures using aluminum screening, which Mayer made to explore formlessness, intending that viewers would not be able to hold a precise image of the

work in mind.

Lucretia in Ferrara 1509, 1973. Colored pencil on paper. 40 x 30 in. Courtesy of the estate of Rosemary Mayer and ChertLüdde, Berlin.

Lucretia in Ferrara (1974) refers to the Italian Renaissance noblewoman Lucrezia Borgia. While a storied figure, there are no known portraits of Lucrezia Borgia. Mayer wrote in her notes that she was interested in referring “to female presences which exist now only in

historical memory.”

The Fifth Angel Sleeve, 1973. Colored pencil, oil paint and gold on wood. 26 1/4 x 20 1/2 in. Courtesy of Peggy DeCoursey.

Solomonic Columns, 1974. Colored pencil and ink on paper. 28 x 23 in. Courtesy of the estate of Rosemary Mayer and ChertLüdde, Berlin.

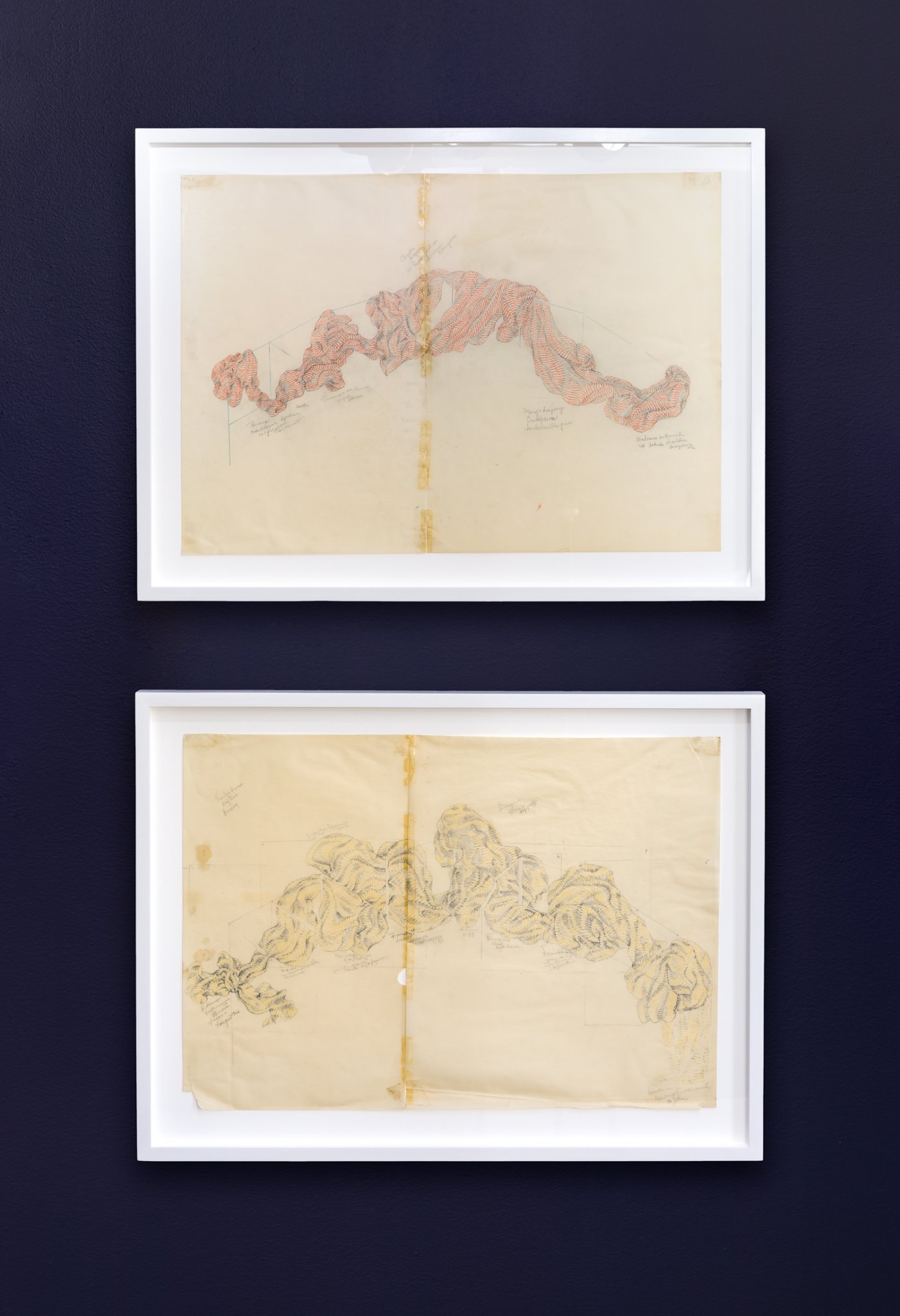

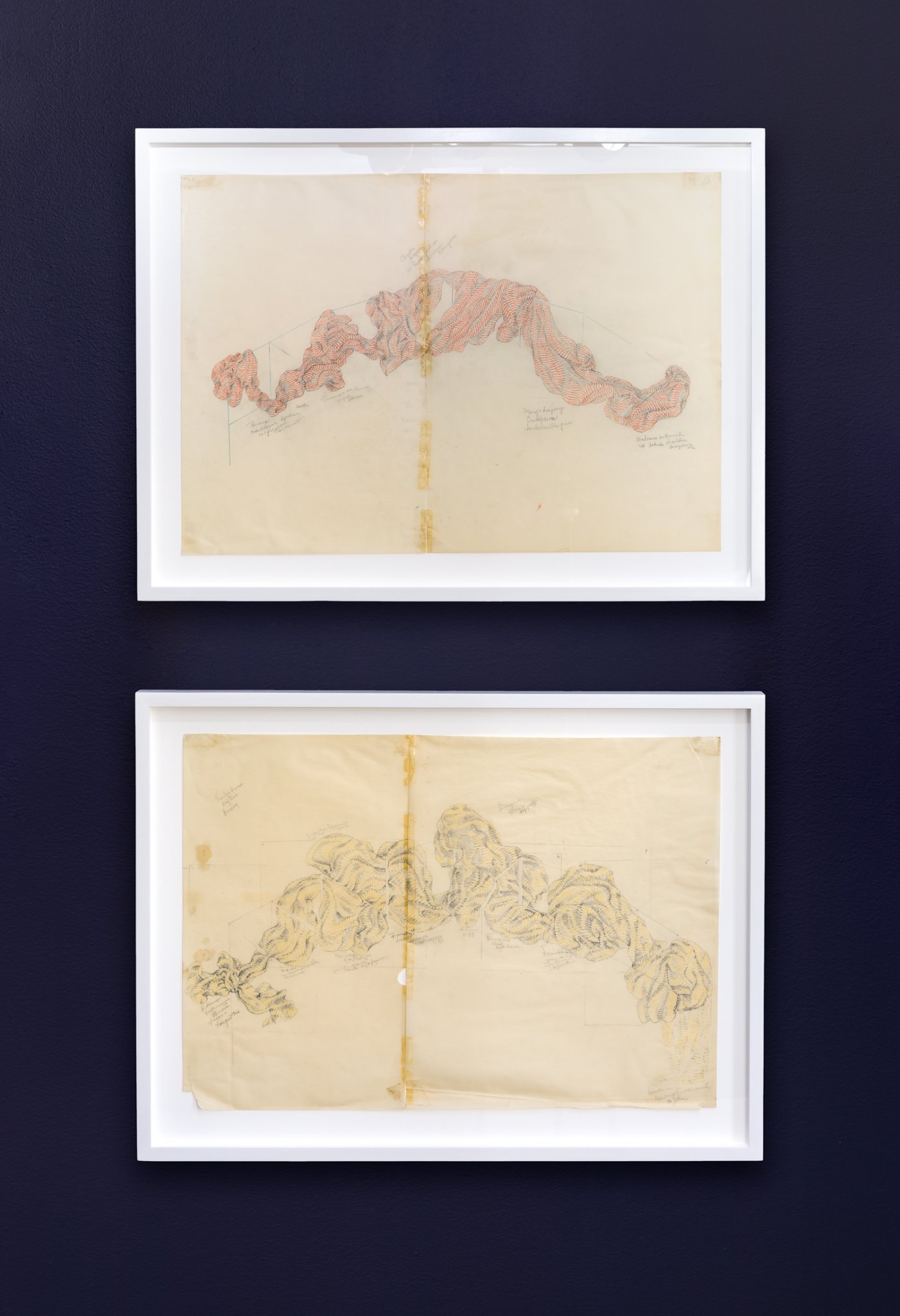

From top:

Fabric for Portae (red), 1974

Marker and pencil on vellum. 2 sheets, left 16 x 7/8 x 11 in; right 16 7/8 x 13 1/16 in.

Fabric for Portae (yellow), 1974. Marker and pencil on vellum. 2 sheets, left: 16 7/8 x 10 1/8 in; right 16 7/8 x 14 7/8 in. Both courtesy of the estate of Rosemary Mayer.

Portae (1974) is a large arched sculpture formed from a wooden frame trellis. With layers of fabric draped over and through it, the work is possibly based on Rosso Fiorentino’s

Volterra Deposition altarpiece (1521), which features a tangled arc of ladders seen above its central crucifix. In these preparatory drawings for the sculpture, Mayer creates a cartography for

the folds of the fabric, drawn from details of late Renaissance paintings including those by

Jacopo Pontormo, Matthias Grünewald and Parmigianino.

Untitled, 1974. Colored ink on paper

19 x 24 in. Courtesy of the estate of Rosemary Mayer and ChertLüdde, Berlin.

Untitled (London), 1975. Watercolor and pen on paper. 12 3/8 x 9 1/2 in.

Untitled (Part of the pinning down of flowers), 1975 Watercolor and pen on paper

15 x 22 in.

Untitled (London), 1975. Watercolor and pen on paper. 12 3/8 x 9 1/2 in.

All courtesy of the estate of Rosemary Mayer.

Following her trip to Europe in 1975, Mayer began connecting her interest in formlessness and dissolution to the work of specific painters such as Pontormo and creating forms in which to express this. She was particularly struck by Pontormo’s drawings for frescoes in the church of San Lorenzo in Florence that depict a mass of entwined bodies dying in a flood. She made a series of watercolors depicting somewhat abstract masses of floral forms, often layered with

text, which she described as “dissolving” and “impossible,” much like her impossible textile

sculptures from a few years prior.

Rosemary Mayer: Ways of Attaching, installation view.

From left:

In Time Order (March / April), 1978. Ink, oil crayon, photograph on paper

23 3/4 x 18 in.

In Time Order (Lady Slipper Orchid), 1978. Ink, oil crayon, photograph on paper. 23 3/4 x 18 in.

In Time Order (May / June), 1978. Ink and oil crayon on paper

23 3/4 x 18 in.

In Time Order (Roses), 1978. Ink, oil crayon, photograph on paper

23 3/4 x 18 in.

In Time Order (Day Lily), 1978. Ink, oil crayon, photograph on paper

23 3/4 x 18 in. All works courtesy of the estate of Rosemary Mayer and Gordon Robichaux, New York.

These five collages are part of a larger, twelve-piece series that forms a calendar of months and seasons. It established Mayer’s renewed focus on time and the seasons during the later 1970s and includes details that would appear in concurrent and subsequent works, including

birthdays, lists of names, flowers in season, constellations and personal memories. Collaged

materials include family photographs and Mayer’s own photography, which featured chandeliers

and opulent décor.

Spell, 1977. Watercolor on paper

26 x 20 in. Courtesy of Ales Ortuzar and Gordon Robichaux, New York.

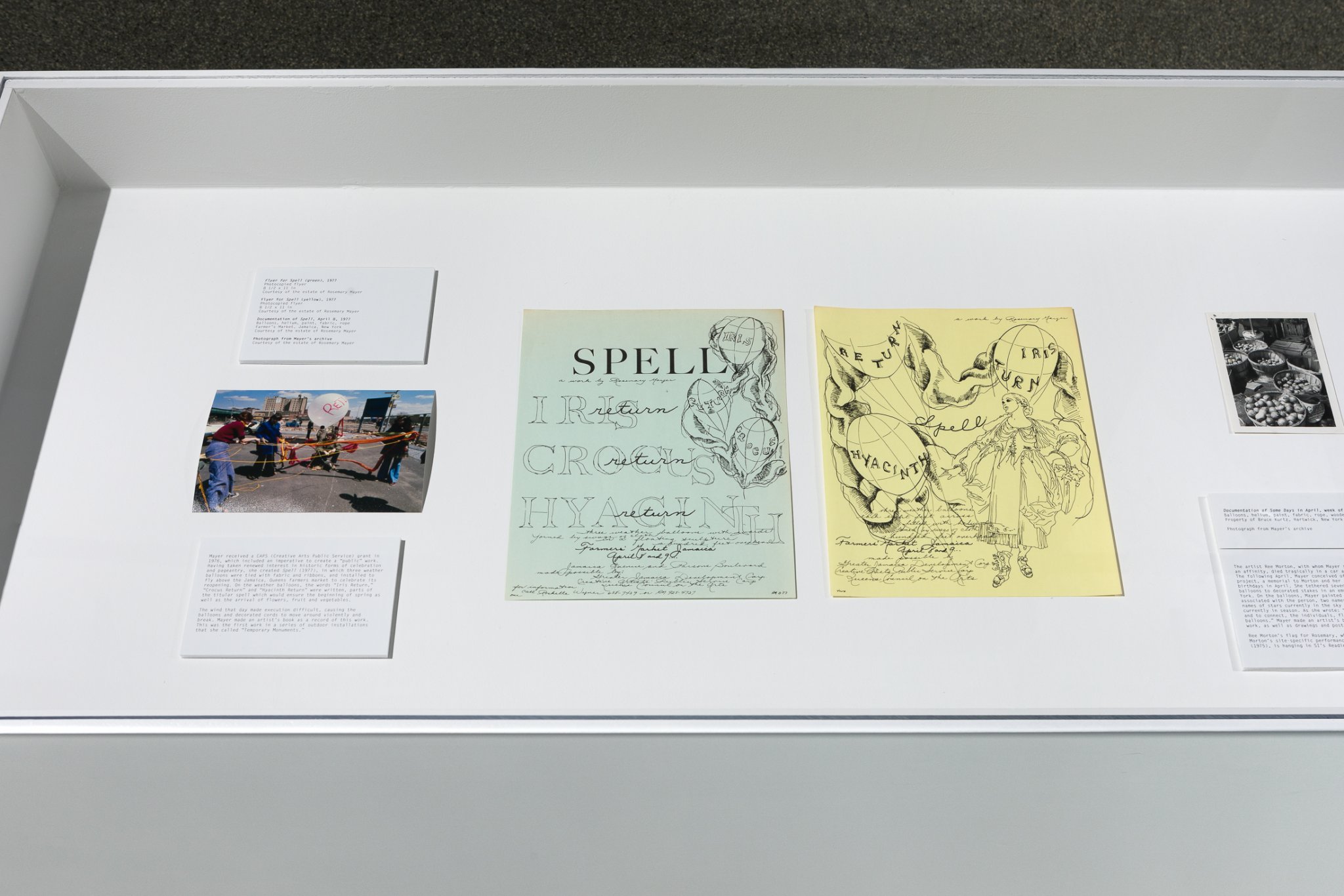

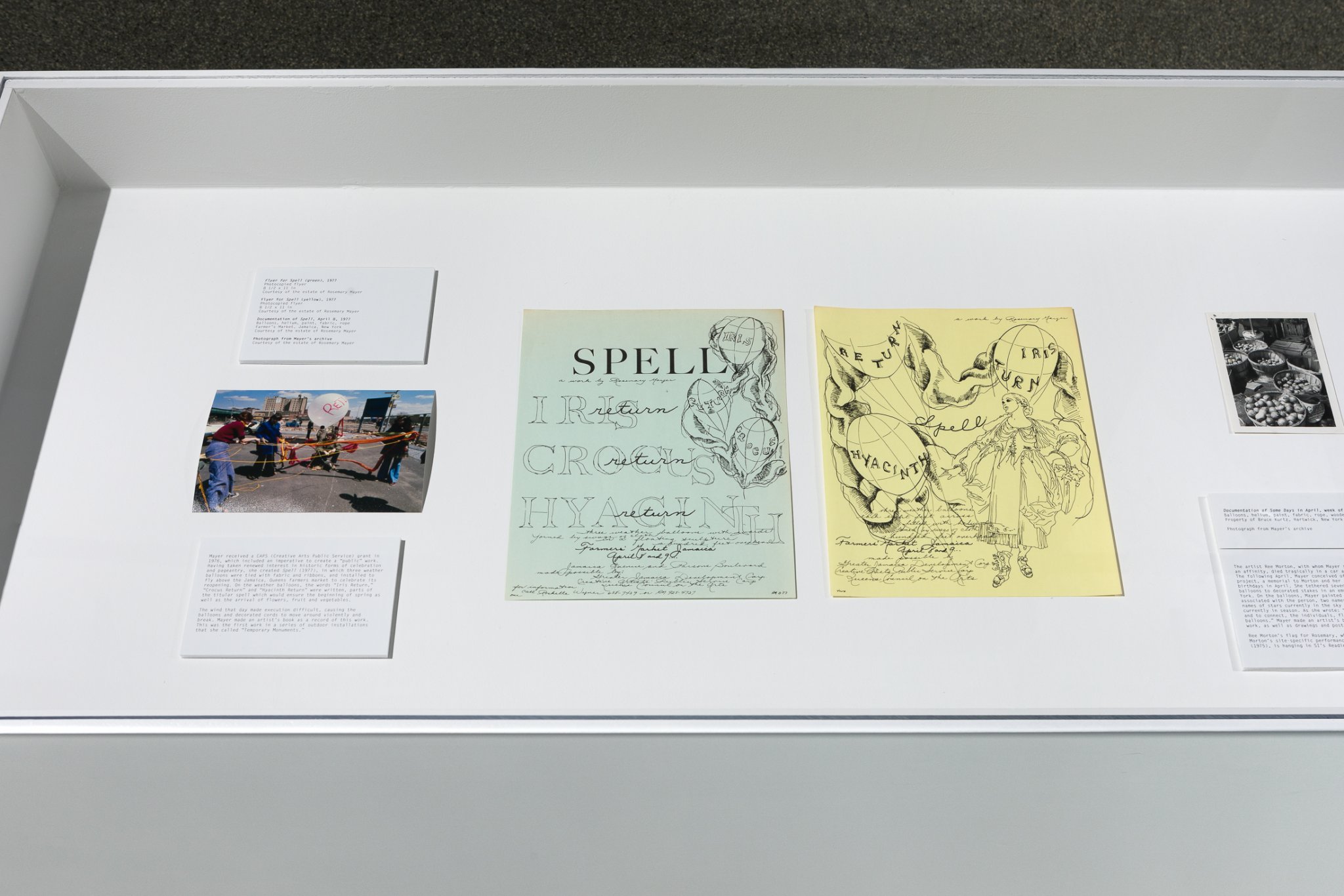

From left: Photograph from Mayer’s archive.

Courtesy of the estate of Rosemary Mayer. Documentation of

Spell, April 8, 1977. Balloons, helium, paint, fabric, rope. Farmer’s Market, Jamaica, New York. Courtesy of the estate of Rosemary Mayer.

Mayer received a CAPS (Creative Arts Public Service) grant in 1976, which included an

imperative to create a “public” work. Having taken renewed interest in historic forms of

celebration and pageantry, she created

Spell (1977), in which three weather balloons were tied with fabric and ribbons, and installed to fly above the Jamaica, Queens farmers market to celebrate its reopening. On the weather balloons, the words “Iris Return,” “Crocus Return”

and “Hyacinth Return” were written, parts of the titular spell which would ensure the beginning of spring as well as the arrival of flowers, fruit and vegetables. The wind that day made execution difficult, causing the balloons and decorated cords to move around violently and break. Mayer made an artist’s book as a record of this work. This was

the first work in a series of outdoor installations that she called “Temporary Monuments.”

Banner for 41st Street Ghost (alternate version), 1980. Oil crayon and paint on rayon

64 x 27 1/4 in. Courtesy of the estate of Rosemary Mayer and Gordon Robichaux, New York.

Mayer’s work was included in

The Times Square Show (1980), a historic exhibition organized by the artists’ group Colab. For the show, she contributed the first sculpture from her Ghost series called

41st Street Ghost, in which she used rods to create a simple frame that was draped with sheets of glassine and plastic. Next to the sculpture was a banner with a list of women’s names. She was interested in the exhibition space’s former use as a massage parlor,

imagining names for women who might have once inhabited the space. The banner exhibited here

is an alternative version from the one that hung in the 1980 exhibition.

Clockwise from top: Some Days in April (Poster), 1978. Ink and watercolor on paper

17 3/4 x 23 1/2 in. Some Days in April, 1978. Colored pencil, pen, and graphite on paper. 26 x 40 in. Both courtesy of the estate of Rosemary Mayer and Gordon Robichaux, New York. Some Days in April, 1978. Watercolor, colored pencil, and ink on paper. 14 x 18 in. Courtesy of Beth Rudin DeWoody and Gordon Robichaux, New York.

Mooring Knot, 1978. Colored pencil and graphite on paper. 15 1/8 x 12 in.

Mooring Knot, 1978. Colored pencil and graphite on paper. 15 1/8 x 12 in

Both courtesy of Beth Rudin DeWoody and Gordon Robichaux, New York.

These drawings depict the knots that held the balloons to their stakes for

Some Days in

April. They appear here as a detailed type of performance documentation.

In vitrine: Documentation of

Some Days in April, week of April 17, 1978. Balloons, helium, paint, fabric, rope, wooden rods. Property of Bruce Kurtz, Hartwick, New York. Courtesy of the estate of Rosemary Mayer. Photograph from Mayer’s archive. Courtesy of the estate of Rosemary Mayer.

The artist Ree Morton, with whom Mayer shared a friendship and an affinity, died tragically

in a car accident in April 1977. The following April, Mayer conceived of another balloon project, a memorial to Morton and her late parents who shared birthdays in April. She tethered seven yellow, white and orange balloons to decorated stakes in an empty field in upstate New York. On the balloons, Mayer painted the date in April associated with the person, two names for each person, the names of stars currently in the sky and the names of flowers currently in season. As she wrote: “The work is a monument for, and to connect, the individuals, flowers, stars, times, on the balloons.” Mayer made an artist’s book as a record of this work, as well as drawings and posters.

Ree Morton’s flag for Rosemary, which flew from a ship for Morton’s site-specific

performance,

Something in the Wind (1975), hangs in SI’s Reading Room.

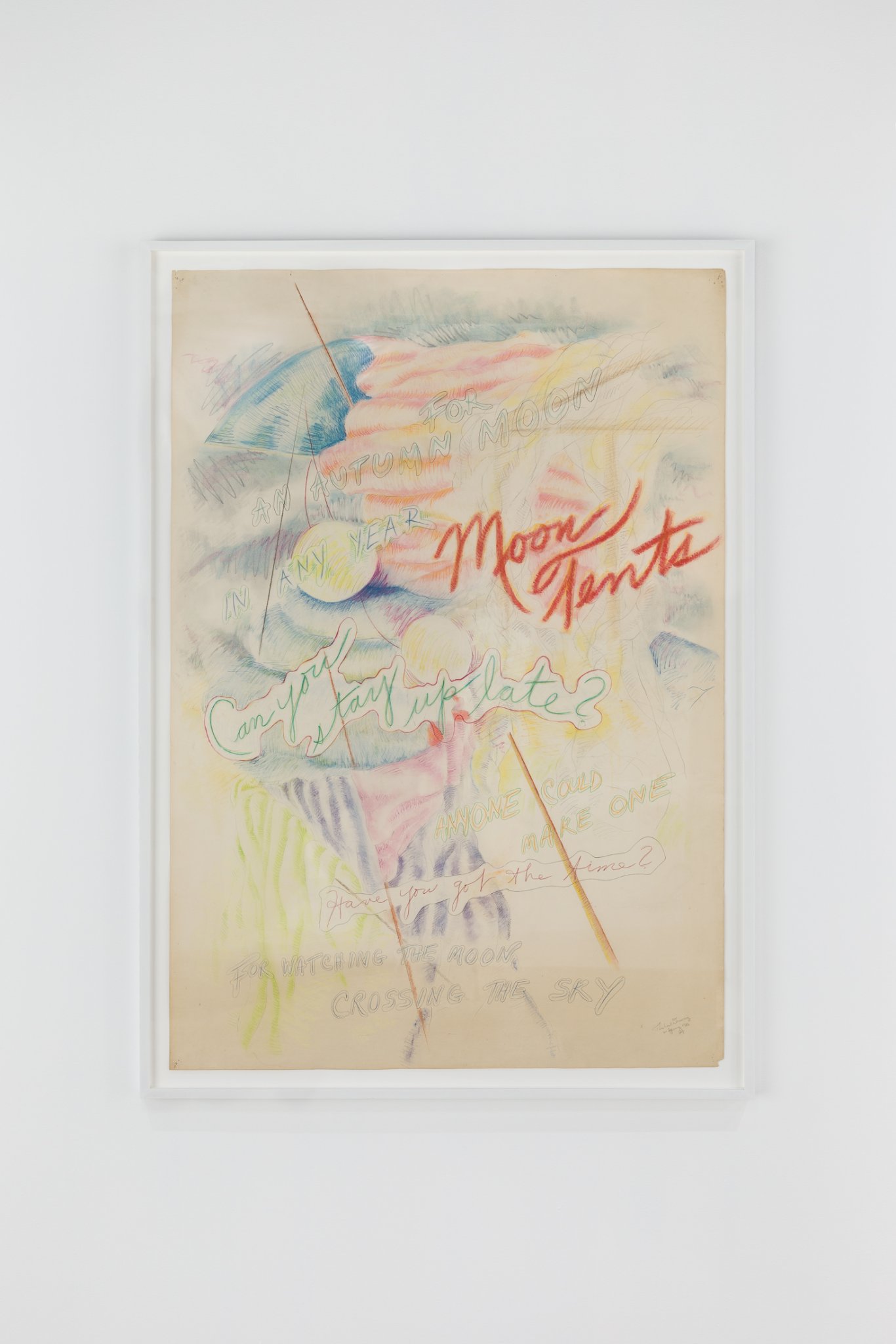

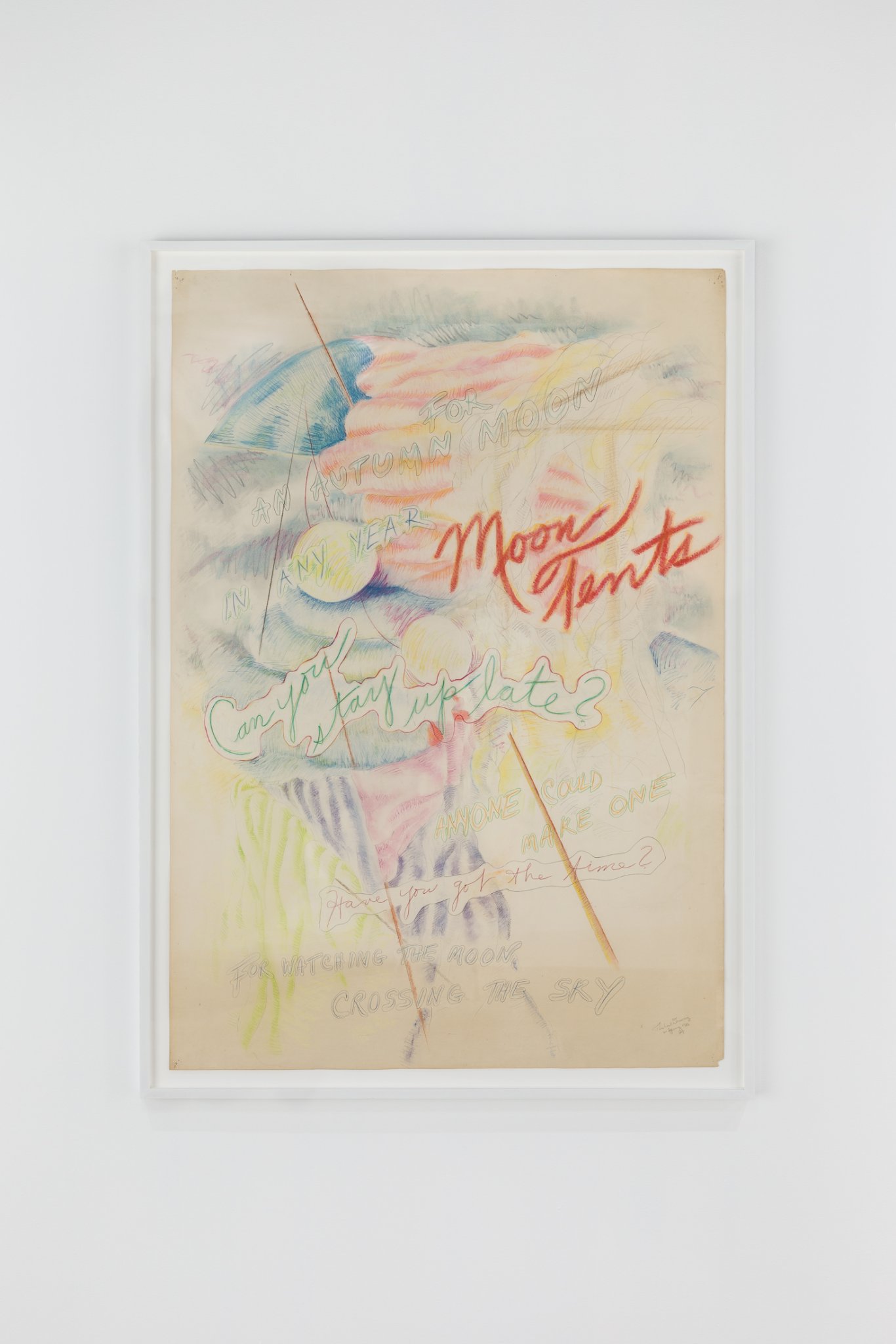

Moon Tents for Autumn Moon, 1982

Watercolor and colored pencil on paper. 61 1/2 x 42 1/4 in. Courtesy of the estate of Rosemary Mayer and Gordon Robichaux, New York.

During the late 1970s, Mayer became interested in tents as a focus for seasonal celebration. She made several works on paper that proposed tents for celebrating the full moon before she created the installation

Moon Tent on the roof of the Hobbs House in Lansing, New York in October 1982. Many of these drawings include repeated refrains that encourage participation: “Do you have the time?”, “Can you stay up late?”, “Anyone can make

one.”

Clockwise from top: Untitled, 1979. Colored pencil and graphite on paper. 23 3/4 x 18 in. Fabric and Cord Tent at a Corner of a Roof for a NYC Building, 1978. Charcoal and pencil on paper. 26 x 35 1/4 in. Banner for a Full Moon Celebration, 1981. Watercolor and pencil on paper. 14 1/4 x 10 1/4 in. All courtesy of the estate of Rosemary Mayer and Gordon Robichaux, New York.

Documentation of

Balloon for a Birthday, November 7, 1978. Balloon, helium, paint, rope, metallic streamers. Rooftop of 461 Park Avenue, New York, New York. Courtesy of the estate of Rosemary Mayer

Mayer created

Balloon for a Birthday to celebrate the birthday of her friend John Campione on November 7, 1978. Mayer decorated the red advertising balloon with metallic streamers and painted the date, together with a seasonal flower “chrysanthemum,” and “Aldebaran,” a red star in the sky at the time. The balloon was flown from the roof of 461 Park Avenue (a building belonging to Campione) and advertised to the public below with flyers designed by Mayer.

Documentation of

Moon Tent, in celebration of the full moon on October 2-3, 1982, 6:43 p.m. to 5:27 a.m. Installation with paper on the roof pavilion of the Hobbs House, Lansing, New York Courtesy of the estate of Rosemary Mayer. Invitation to

Moon Tent, 1982

Printed postcard. 4 x 6 1/4 in. Courtesy of the estate of Rosemary Mayer.

Mayer made Moon Tent (1982) at the home of the art historian Robert Hobbs in Lansing, New York. There she wrapped an existing rooftop pavilion with pale glassine paper and invited viewers to watch the moon on the night of October 2-3, 1982. The glow of the full moon was to light the paper, creating a temporary phenomenon that would disappear the next day. Mayer described it as a “ghost tent, proliferating ghosts and the ghosts of tents in changes of light.”

From left:

Icy Dark Broke, 1983. Watercolor and pencil on paper. 30 x 22 1/4 in.

When, 1983. Watercolor, colored pencil, and pencil on paper. 31 1/8 x 23 1/4 in.

Noon Has No Shadows, 1983

Watercolor and pencil on paper. 30 x 22 1/4 in.

All courtesy of the estate of Rosemary Mayer and Gordon Robichaux, New York.

In 1983 Mayer began making watercolor still lifes of flowers and adding bold text to them,

rather than the notational scripts that she had previously employed to incorporate writing

into her paintings. In her journal she characterized the combination of words and imagery that she used to make these works as “plain desperate words and beautiful objects.” Several of the phrases summon various states of security and fragility. She later began to incorporate images of vessels into these paintings, leading to a subsequent series of large

sculptural vessels.

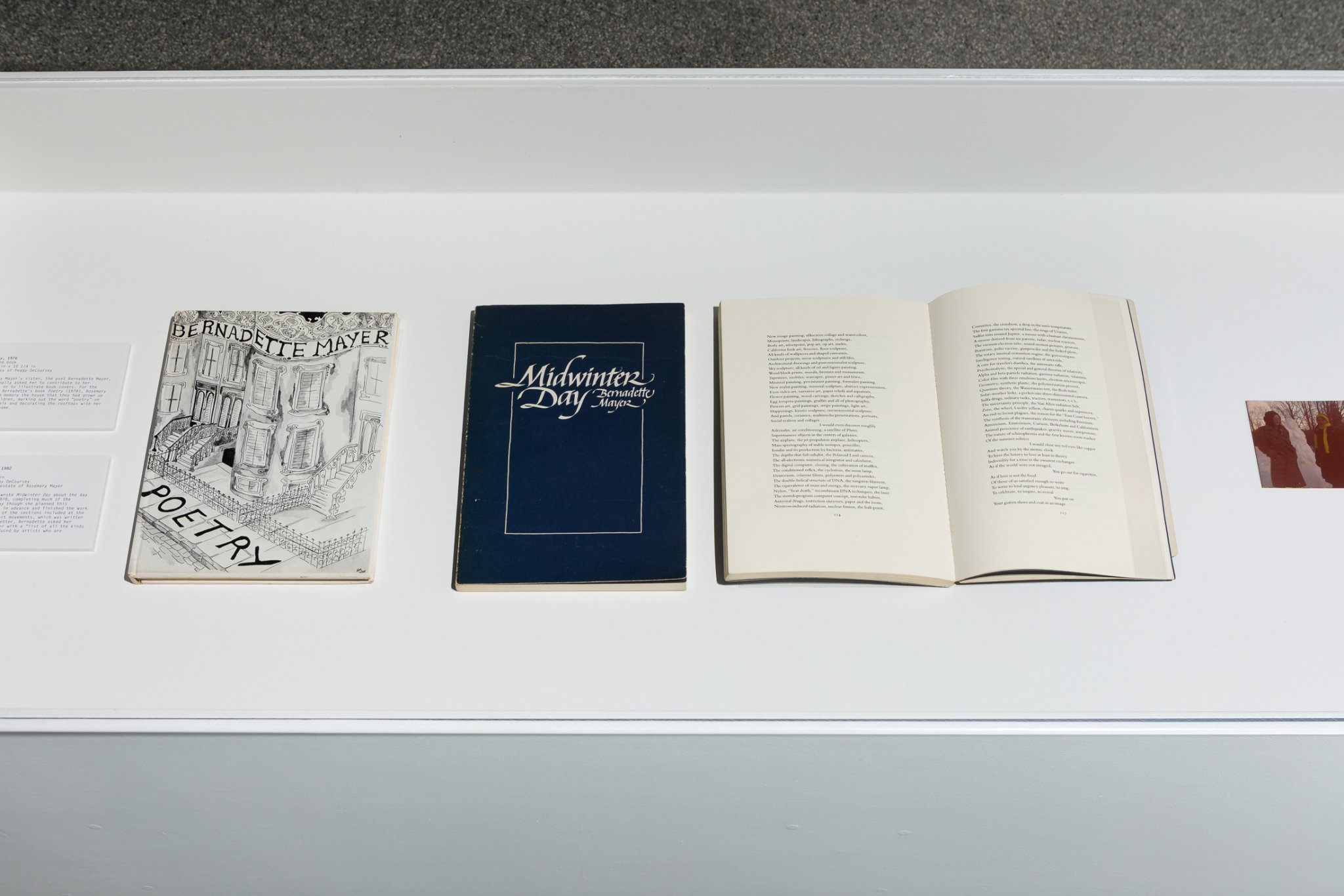

From left:

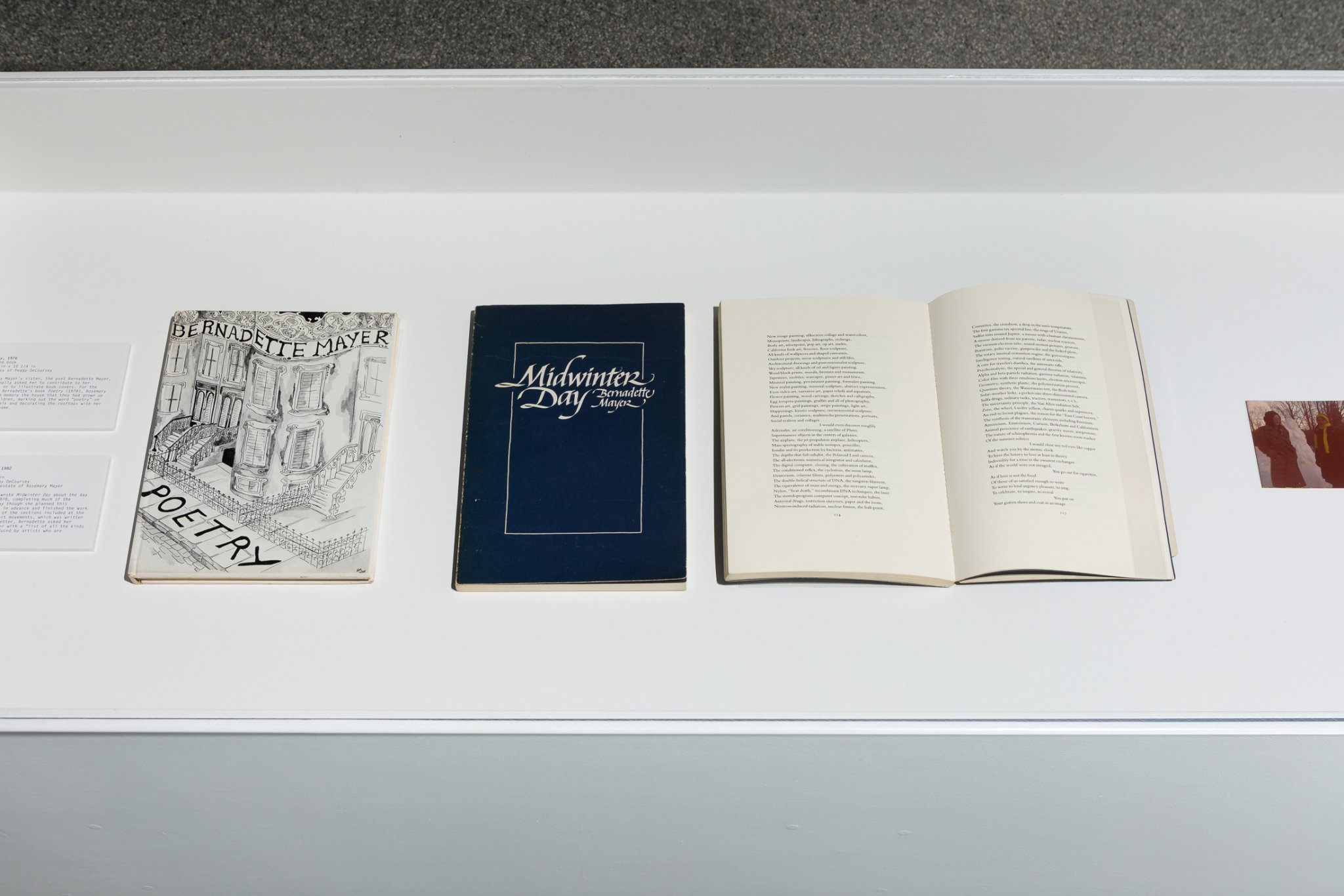

Poetry, 1976. Printed book.

7 1/2 in x 10 1/4 in. Courtesy of Peggy DeCoursey.

Rosemary Mayer’s sister, the poet Bernadette Mayer, occasionally asked her to contribute to her projects or to illustrate book covers. For the cover of Bernadette’s book

Poetry (1978), Rosemary drew from memory the house that they had grown up in as children, marking out the word “poetry” on the sidewalk and decorating the rooftops with her sister’s name.

Midwinter Day, 1982. Printed book. 7 1/2 x 10 3/4 in. Courtesy of Peggy DeCoursey.

Midwinter Day, 1982. Printed book. 7 1/2 x 10 3/4 in. Courtesy of the estate of Rosemary Mayer.

Bernadette Mayer wrote

Midwinter Day about the day of December 22, 1978, completing much of the writing on that day though she planned this endeavor for weeks in advance and finished the work early in 1979. One of the sections included at the end was a list of art movements, which was written by Rosemary. In a letter, Bernadette asked her sister to provide her with a “list of all the kinds of things being produced by artists who are contemporary.”

From left: Rosemary Mayer and Bernadette Mayer with

Snow People, 1979. Courtesy of the estate of Rosemary Mayer. Documentation of

Snow People, February 1979. Snow, wood, paint. Garden of the Lenox Library, Lenox, Massachusetts. Courtesy of the estate of Rosemary Mayer.

Mayer made

Snow People in the garden of the Lenox Library, while her sister, Bernadette, was living in the town of Lenox, Massachusetts. For this work, Mayer sculpted fifteen figures from snow, fashioning them with nineteenth century silhouettes. Researching common names from the town’s past inhabitants, she dedicated each snow person, plurally, to a set of people with a shared name. At the feet of each snow sculpture was a painted wooden sign, reading “Carolines,” “Fannys,” “Sarahs,” and so on.

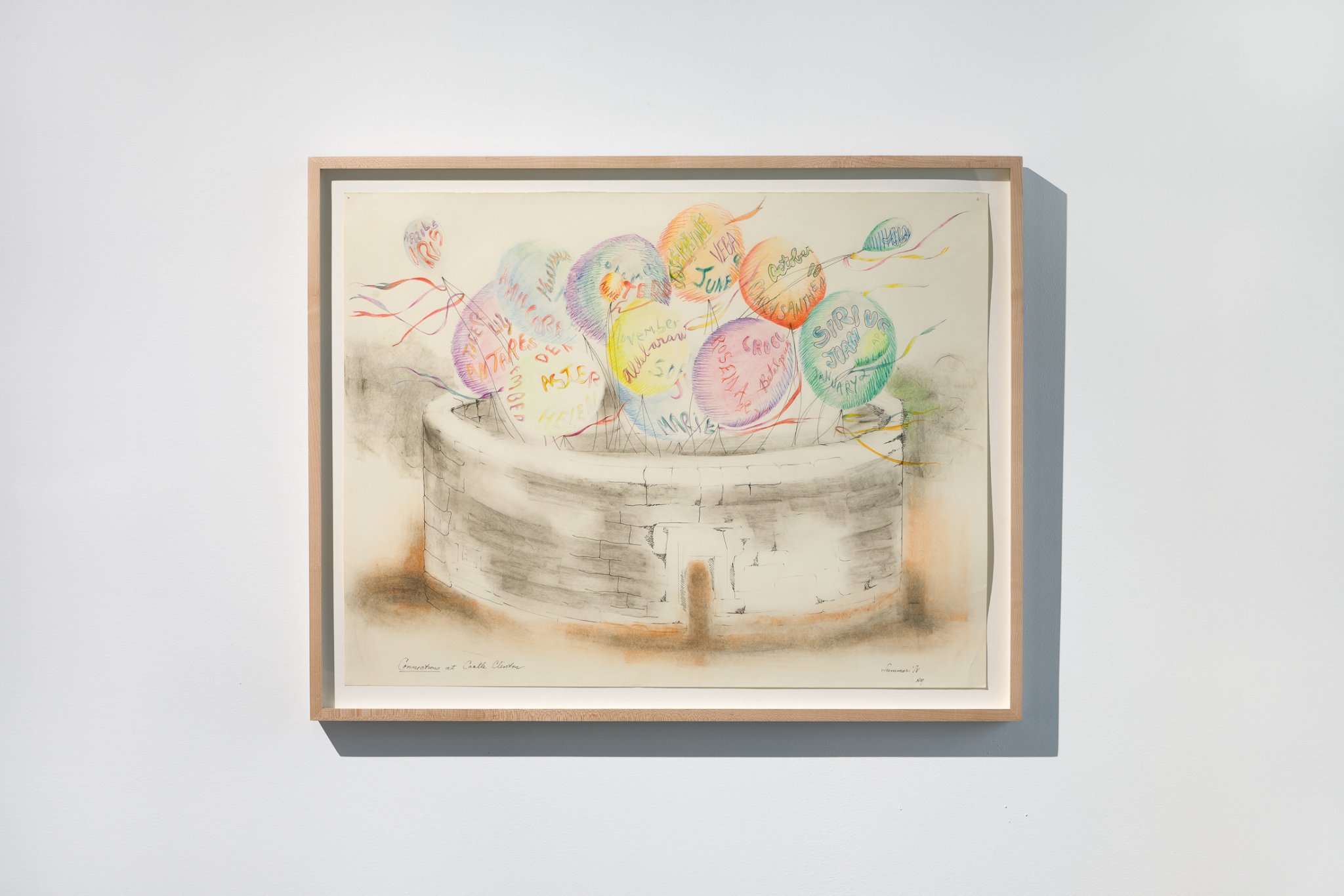

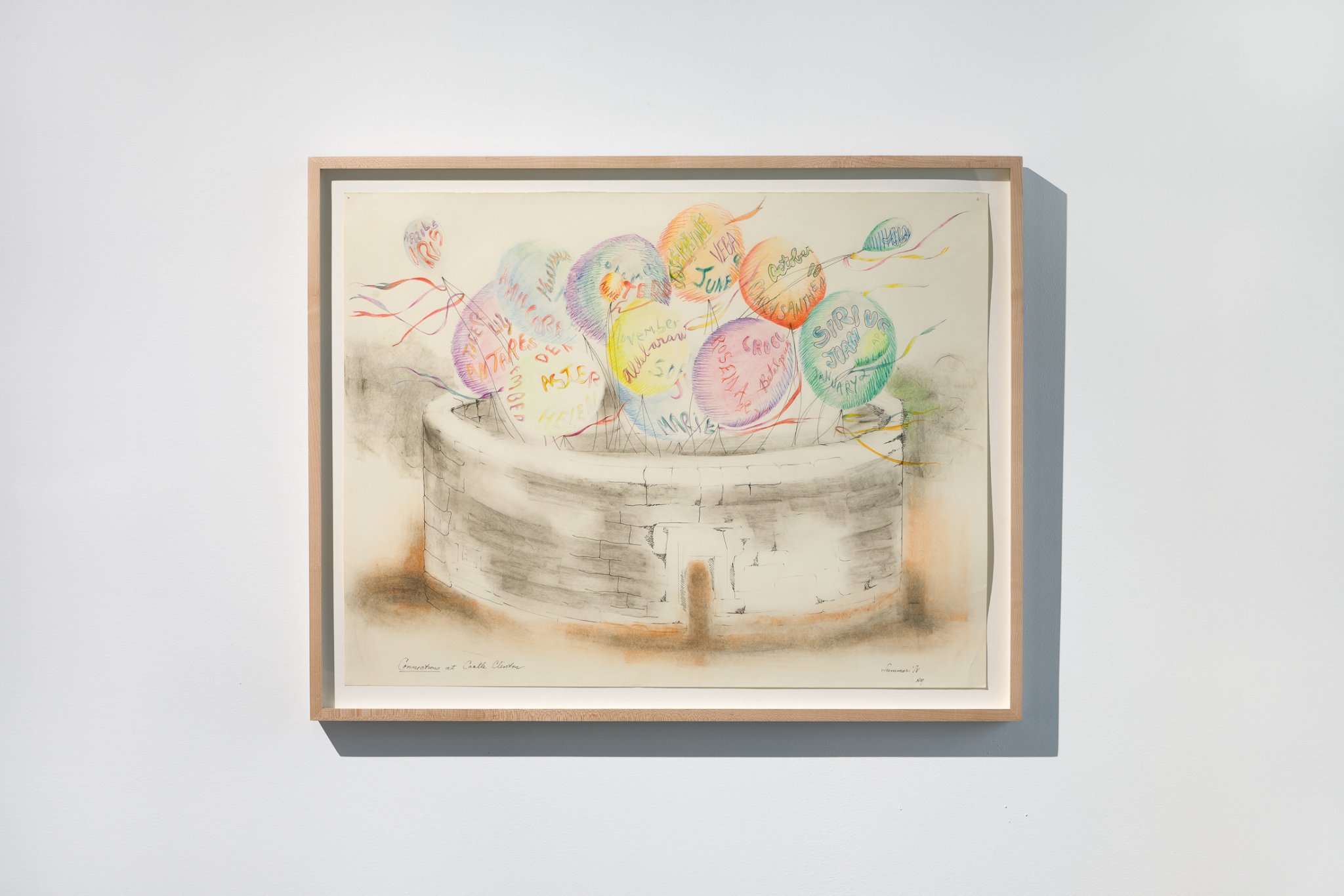

Connections, 1978. Colored pencil, graphite, charcoal on paper. 20 x 26 in. Courtesy of Beth Rudin DeWoody and Gordon Robichaux, New York.

Not all Mayer’s “Temporary Monuments” were realized, and many remain as drawings or becamewhat she termed “impossible sculptures.” For a proposed work called Connections, she planned to fill Castle Clinton, an old fort in Battery Park, with balloons, on which children would

paint tributes using her system of name, date, star and flower. As it becomes more likely

that the work would not be made, she wrote to her sister that at least it would “lead to some

good drawings.”

Rosemary Mayer: Ways of Attaching reference room. Hanging: Ree Morton, Rosemary's flag from Something in the Wind, 1974. Acrylic and felt-tip pen on nylon. 24 1/2 x 31 in. Courtesy of the estate of Rosemary Mayer.

Rosemary Mayer: Ways of Attaching reference room featuring video of interviews with Jacki Apple, Donna Dennis, Harmony Hammond, Bernadette Mayer, Grace Murphy, Marie Warsh, Max Warsh and Martha Wilson. Filmed 2021.

![]()