Dora Budor: Spring | Cura.

Jul 01 2020

DORA BUDOR

Breathes the Future

by Flora Katz

We were not breathing in the ’80s and ’90s: “No Future,” claimed the punks, “There Is No Alternative,” stated Thatcher. Imprisoned in an everlasting present, the postmodern generation has long denounced the impossibility of telling of the past and imagining the future. Stuck in concrete blocks, in utopian bubbles, nothing could pierce the present. There was talk of the end of great storytelling and of the infallibility of capitalism. Art responded with depthless shapes and simulacra. How could the present be unlocked to possible realistic alternatives? What device could today open the valves and let us breathe the future?

If this question prompts us to look for concrete answers, it may also be approached from a formal point of view. It is in fact a question that is part of the practice of Dora Budor and of an increasing number of artists and thinkers looking for alternatives to the closure of possibilities. Their answer is to create moving forms that ally with real exterior determinations and speculative narratives filled with unexpected events. A few months ahead of Budor’s exhibition at Kunsthalle Basel, here is an analysis of a small body of her works in the light of the progressive unveiling of these forms.

Towards the organic body

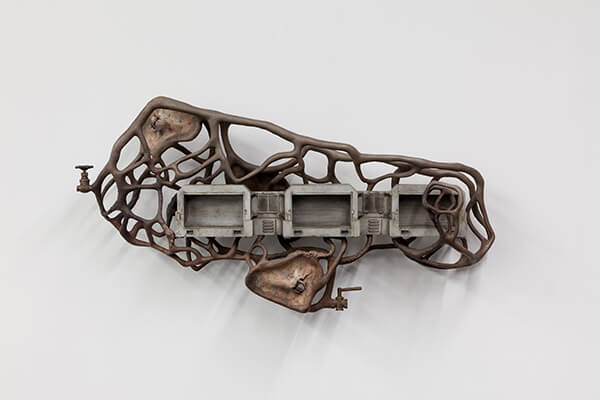

In Spring, presented in 2015 at the Swiss Institute (New York), the artist intersperses a few cityscape models from the films The Fifth Element, Johnny Mnemonic and Batman Returns in heating systems equipped with pipes that echo blood vessels. Immediately, the Cronenbergian atmosphere emerges: the works have an organic aspect, ready to project us into another dimension, just as real as ours. The environment of the sculptures is represented by a black viscous floor that extends onto the wall: it recalls the matter that has activated on the bodies of the Chinchorro mummies because of the rise in average temperatures over the last years. While the textures of Spring mimic organic elements, they still remain inactive.

It is through the action of time that the movement progressively integrates, in particular through climate. In The Forecast (New York Situation) (2017), a sculpture set up on the New York High Line is transformed under the action of the rain: playing again with the pipe-like shape of blood vessels, it connects soft-looking resin containers which resemble body organs. When it rains, what is inside them reveals itself: the prosthetic materials made to be used in scenes of biological mutations in films (from weeds to fish scales and other various plant-like growths), collected on film sets, are immersed in ochre colors, yellows tending to gray and dark green. The general structure is inspired also by architecture and hints at the Living Pods, nomadic dwellings, independent yet connected to each other, designed in the 1960s by David Greene for the British collective Archigram. The environment thus becomes an external, contingent agent that complements the piece. In a perpetual modulation, its movement is that of the real world itself.

This feature must be taken seriously: an artwork that is one with a contingent environment proposes a particular form in the history of art. Neither an installation nor a performance, it reverses the definition of the work as immutable and eternal. It borrows its entropic play from Land Art, meanwhile placing itself within the institution. Reacting to everything it touches, the piece is so close to the realm of reality that it can transform itself, be born again and even die.

A reacting work of art

The idea of an artwork as a lung of its environment can also be found a year earlier in an important group exhibition on immersive cinema (1): inside a large metal cube, one discovers a dark space (Adaptation of an Instrument, 2016). From the floor, green light rays rise up to the ceiling, as if the floor’s energy were spreading through blood vessels. Above, we see halos of lights and shadows that sometimes make appear frog bodies. These were the original items taken from the scene of Paul Thomas Anderson’s film Magnolia (1999), in which frogs suddenly fall from the sky during the night. This fantastic scene is placed in the middle of a realistic movie, in which the characters gradually lose control of their lives. The absurdity of the scene fascinated Dora Budor: the irruption of a contingent event reveals the whole dynamic of the movie and is as well a take on the potential irrationality of life. On the ceiling surface the gray-green light turns to white, suggesting a dense aquatic world like that of a marsh. We also hear sounds that are at the same time clear and confused, echoes of the outside world. At certain moments, the light rays flicker: they materialize the liveliness of the piece, reacting to the movement of the visitors as a neuronal organism.

In 1815, on Mount Tambora in Indonesia, the most explosive volcanic eruption ever recorded took place (about ten thousand times more powerful than the nuclear explosions of Hiroshima and Nagasaki). The eruption spread gas, ashes and pumice stones everywhere, reaching the stratosphere with an altitude of over 43 km. The climatic consequences were disastrous and caused the so-called “Year Without a Summer” all over the Western Hemisphere. Crops were almost completely absent, with frost and cold throughout Europe and Canada. Within a clinical and frozen atmosphere, ash falls covering faded colored furnishings (Year Without a Summer, 2017). The rhythm of the ash falling depends on the sounds produced in space. Made aware of their own impact on the piece, visitors can lower the tone of their voice to avoid the disappearance of the furnishings. The furnishings are the very rare surviving pieces from the 1965 “Landscaped Interior” by the Danish Verner Panton, aiming at conditioning the relationships between those who used them.

Complex systems

Untilled, a piece by the artist Pierre Huyghe, also featured a certain quantity of abandoned objects. Arranged but not exhibited, these were left around the environment, in the compost of Karlsaue Park in Kassel (dOCUMENTA 13, 2012). Under the action of the rain, the pink paint on Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster’s bench kept dripping into a puddle, reappearing on the paw of a spooky dog called Human, which looked tainted. In this place where things are absorbed by the warm compost, the cycles of birth and death are intensified. Pierre Huyghe is probably among the most influential artists for Dora Budor’s generation. In his complex systems, as he himself defines them, each element is put in interdependency with the other, including elements of the space: in After ALife Ahead (2017), presented at the Skulptur Projekte in Münster, an incubator of HeLa cancerous cells is connected to the glass walls of an aquarium, which lighten or darken depending on the evolution of the cells. A shell influences an automated opening on the ceiling. Even the virtual reality, taking the motifs of the ceiling as black pyramids, reacts following the cancerous cell, to, in its turn, influence another real element.

Chain reactions, translations of the passage of a movement, chaos theories imbued with contingencies. A present caught in its randomness by imagined futures and recurring pasts. These features, typical of any complex systems (for example, a society, Wikipedia, an embryo are all complex systems), become more meaningful in The Preserving Machine (2018), Budor’s most recent piece. In the exhibition space, dust sticks to our shoes. It comes from the inner courtyard lit by a yellow and dusty light. The intense orange-yellow colored Australian dust storm of 2009, comes to mind, as do the many yellow sunsets by William Turner. Unreachable futures and pasts coexist: the dust in fact consists of fossil particles. Memory becomes movement: in the courtyard a bird flies irregularly. Getting closer, we notice the bird is mechanical: its trajectory is the transposition of a score by the composer Edvard Grieg, as if it were the remnant of a memory.

For her exhibition at Kunsthalle Basel, Budor will continue with her translation operations, using architecture and music as her means. Invisible elements will become palpable, particularly through vibration. The work is intended to function as an instrument, acting over the scale of the whole museum. To open up to the future, it is necessary to dig into the folds of the present, give it depth and expand it: what happens here has consequences elsewhere. What happened yesterday is still here today. Circular time that breathes, everything coming back like the echo of a sound that has turned into a movement. The future is not trapped in utopia: we are the ones that cage it in a present of which we don’t see the folds.

What futures are we breathing?

Yet, we cannot stop here: what are the folds made visible by Budor? Concrete narratives can be found behind the formal analysis of these works. A mechanical bird, a dusty yellow light, a viscous black matter that pervades mummified bodies, abandoned furniture: all these elements convey the lexical field of a world abandoned by humans. Because observing the future from the real world of 2019 moves man away from the center of the landscape. This is not a dystopia, but a realistic future that takes into account the ending of resources, climate change, the extinction of species and so on. If Dora Budor creates works that insist on the form of movement, from complex system to morphing matter, it is probably because she is exploring life, beyond human. Likewise, contemporary philosophers under the umbrella of realism, while immersing themselves in matter (Ray Brassier, Tristan Garcia, Quentin Meillassoux, among others), express a thought which goes beyond human.

So, what to conclude? If we open the possibilities, could it be that are we facing the end of industrialized human society and the very extinction of human? We must be careful: in many of these works contingency, i.e. what happens but cannot be predicted, is an essential element. From a philosophical point of view, it represents the very rib of speculative realism and historically-engaged philosophies like those of Sartre or Deleuze. From the perspective of art, it is the rain, the air, the movement of visitors that give the art piece a transformative ability. In his book on capitalist realism, the theoretician of postmodernity Mark Fisher explains: it is contingency that makes “what was previously deemed to be impossible seem attainable” and “what is presented as necessary and inevitable [is] a mere contingency.”(2) Understanding that we are part of a world in which causality outdoes us is an idea both distressing and full of hope, but in my opinion it is a way to open a breach in our present, and finally breathe.

1. Dreamlands: Immersive Cinema and Art, 1905–2016, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, October 28, 2016 – February 5, 2016, curated by Chrissie Iles.

2. Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism, Is There No Alternative? (Alresford: Zero Books, 2009).

DORA BUDOR (b. 1984, Zagreb, Croatia) is an artist based in New York. Her recent and forthcoming solo exhibitions include: Kunsthalle Basel (2019); 80WSE, New York (2018); Ramiken Crucible, New York (2016); and Swiss Institute, New York (2015). Budor participated in group exhibitions at: Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk; Palais de Tokyo, Paris; David Roberts Art Foundation, London; Kunsthalle Biel; La Panacée, MoCo (Montpellier Contemporain); Fridericianum, Kassel; Künstlerhaus Halle für Kunst & Medien, Graz; K11 Art Museum, Shanghai; as well as 9. Berlin Biennale, Vienna Biennale, Art Encounters 2017, Baltic Triennial 13, and forthcoming 16th Istanbul Biennial.

FLORA KATZ is an art critic, curator, and PhD student at Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne. Her research revolves around Speculative Realism philosophies and contemporary art, with a focus on Pierre Huyghe’s work. She has curated projects such as: Nothing Belongs to Us: To Offer, Fondation d’entreprise Ricard, Paris (2017); Editathon Art+Feminisms, Lafayette Anticipations, Paris (2015-17); Odradek, Instants Chavirés, Montreuil (2015). She is part of the project Free University at DOC (Paris).