Louise Bonnet and Elizabeth King: De Anima

May 07 - Sep 07 2025

Swiss Institute (SI) is pleased to present De Anima, an exhibition that brings together, for the first time, the work of Louise Bonnet (b. 1970, Geneva) and Elizabeth King (b. 1950, Ann Arbor). Bonnet’s paintings often depict bodies suspended between grotesque physicality with symbolic foreboding, and simultaneous subjugation by external forces. King’s sculptures and animations are made in search of the most lifelike shapes and movements, while her research into Renaissance automata posits them as the precursors to today’s mimetic intelligence technologies. While passing as all-too-human, these lack true life force, though not influence. The result of a year-long dialogue between the artists, initiated on the occasion of the exhibition, De Anima pushes against the boundaries between life and nonlife, vitality and passivity, and substance and gesture, in relation to art, technology, and gender.

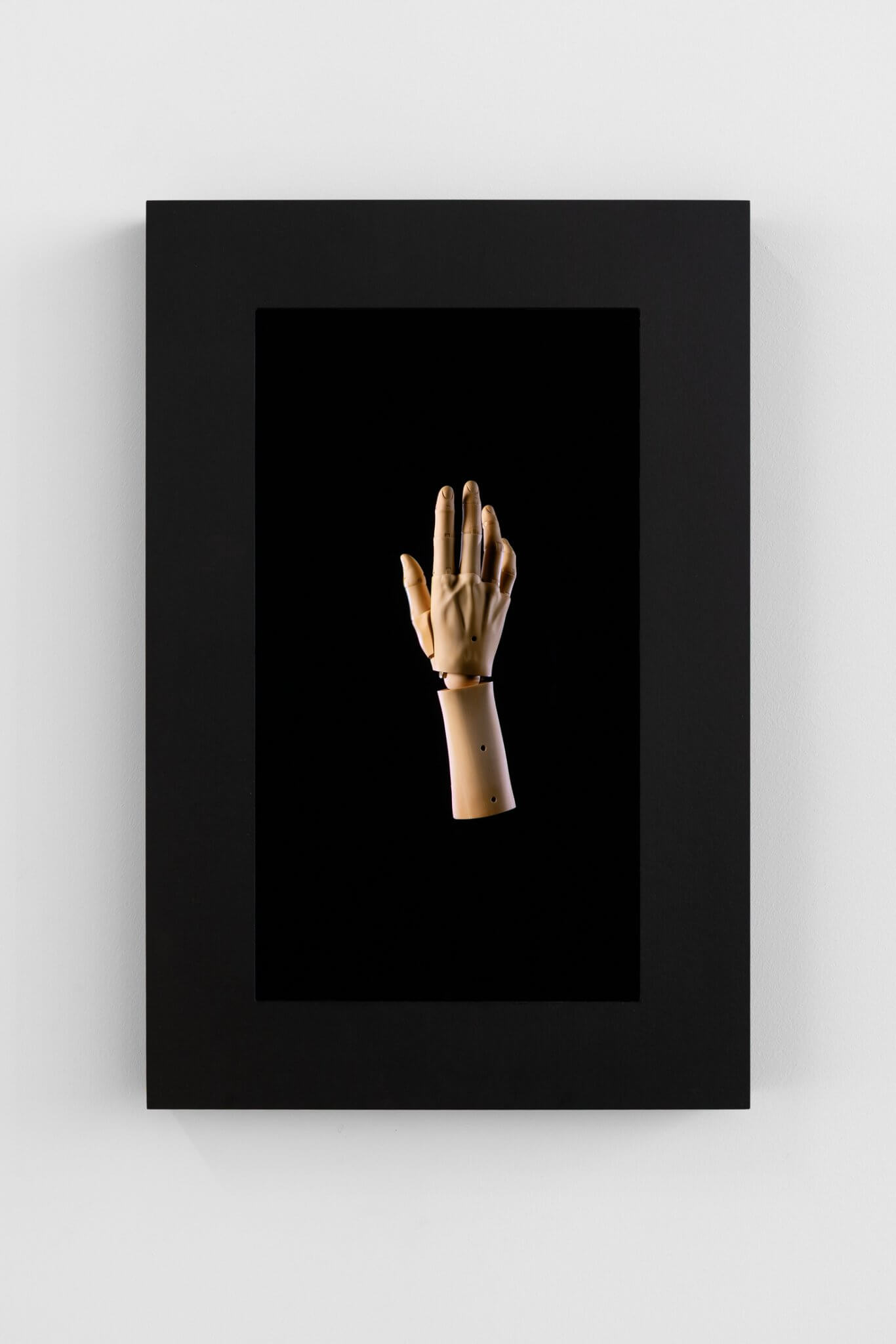

For over fifty years, Elizabeth King has produced sculptures that examine the human form, drawing inspiration from 16th-century mechanical robots, mannequins used in commercial displays or to replace the live model in painting, and jointed figures such as puppets and medical models. At the entrance of the exhibition, visitors are greeted by Bartlett’s Left Hand (2005)—a meticulously carved English boxwood hand, half life-size, mounted on a stand used for stop-motion animation. On the reverse side of the wall, a video displays the same hand pointing, turning, and flexing its jointed fingers, which are precisely crafted to enable its uncannily realistic gestures. Nearby, the earliest work in the exhibition, Untitled Articulated Figure (1974–78), is composed of a bronze skeleton with a porcelain head, glass eyes, and human hair. Suspended within a cedarwood frame, the figure is carefully posed, akin to the art of puppetry, to evoke the most lifelike appearance. Housed in various vitrines is a dramaturgy of additional sculptures, including Untitled (1993), a porcelain head with glass eyes that emits a subtle glow from within. What Happened (1991/2008), a stop-motion animation originally shot on 35mm film in the Colossal Pictures studios in San Francisco, screens in a nearby room. The film consists of vignettes of King’s sculpture Pupil (1990), posed in fleeting passages that suggest a mind discovering its own body.

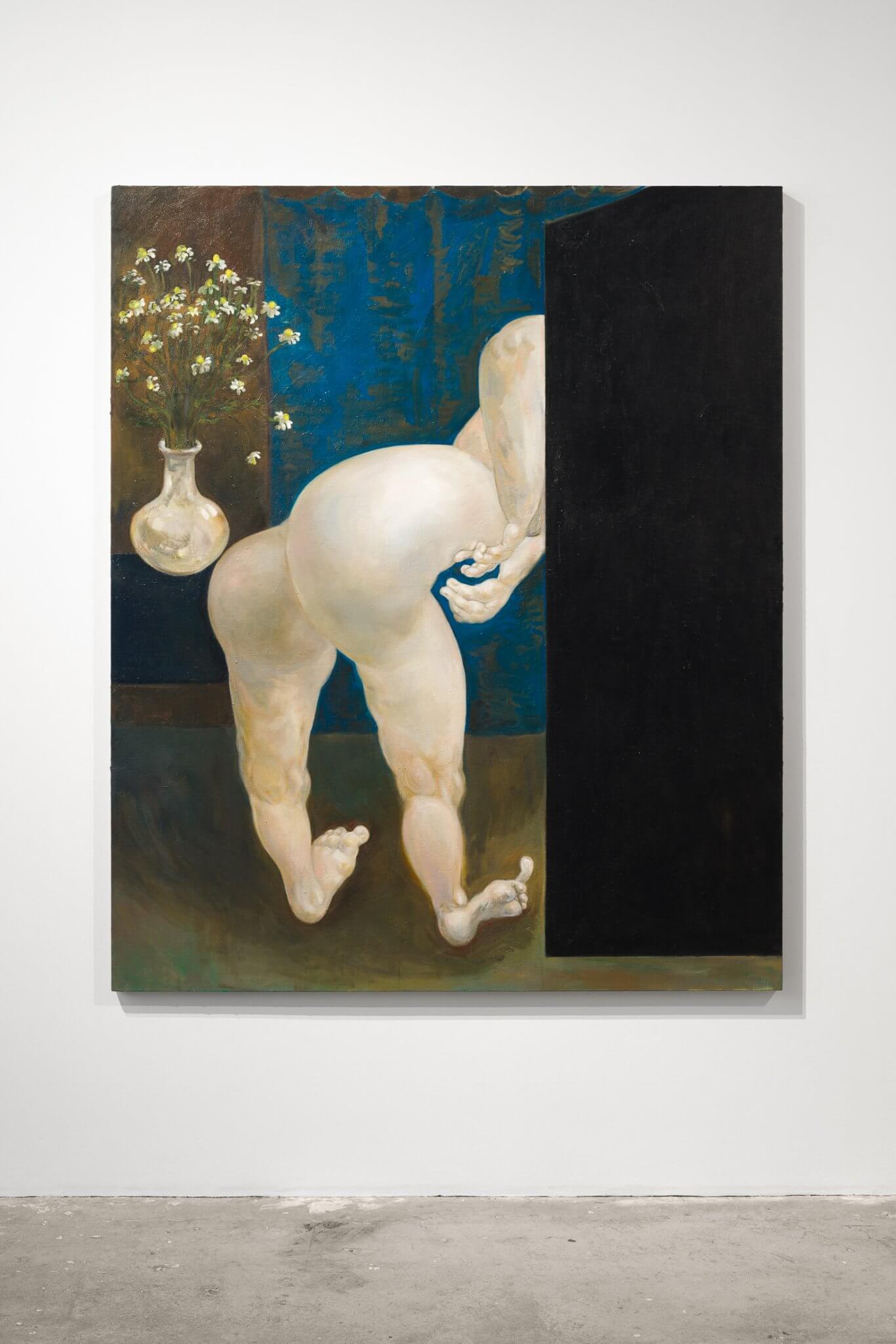

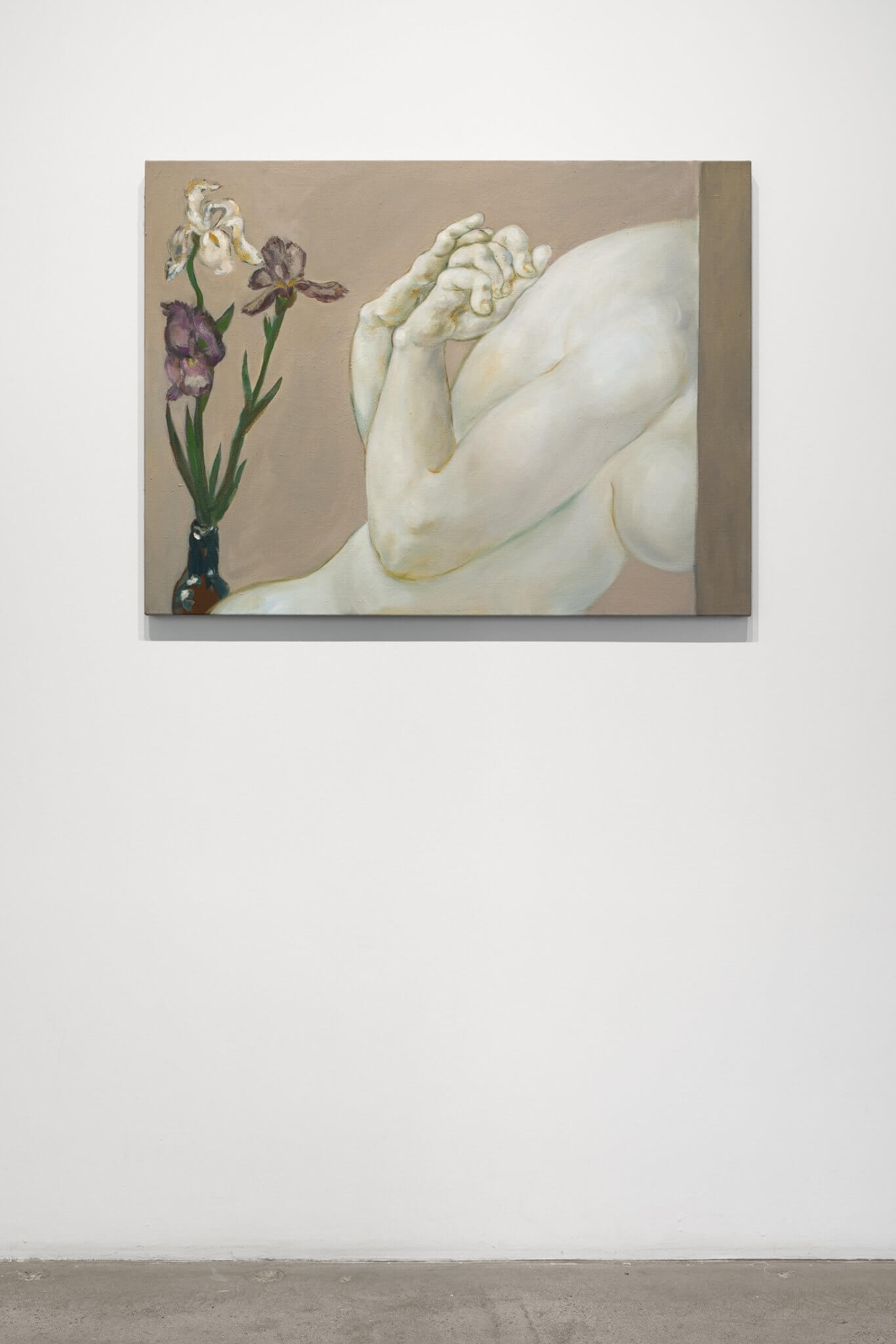

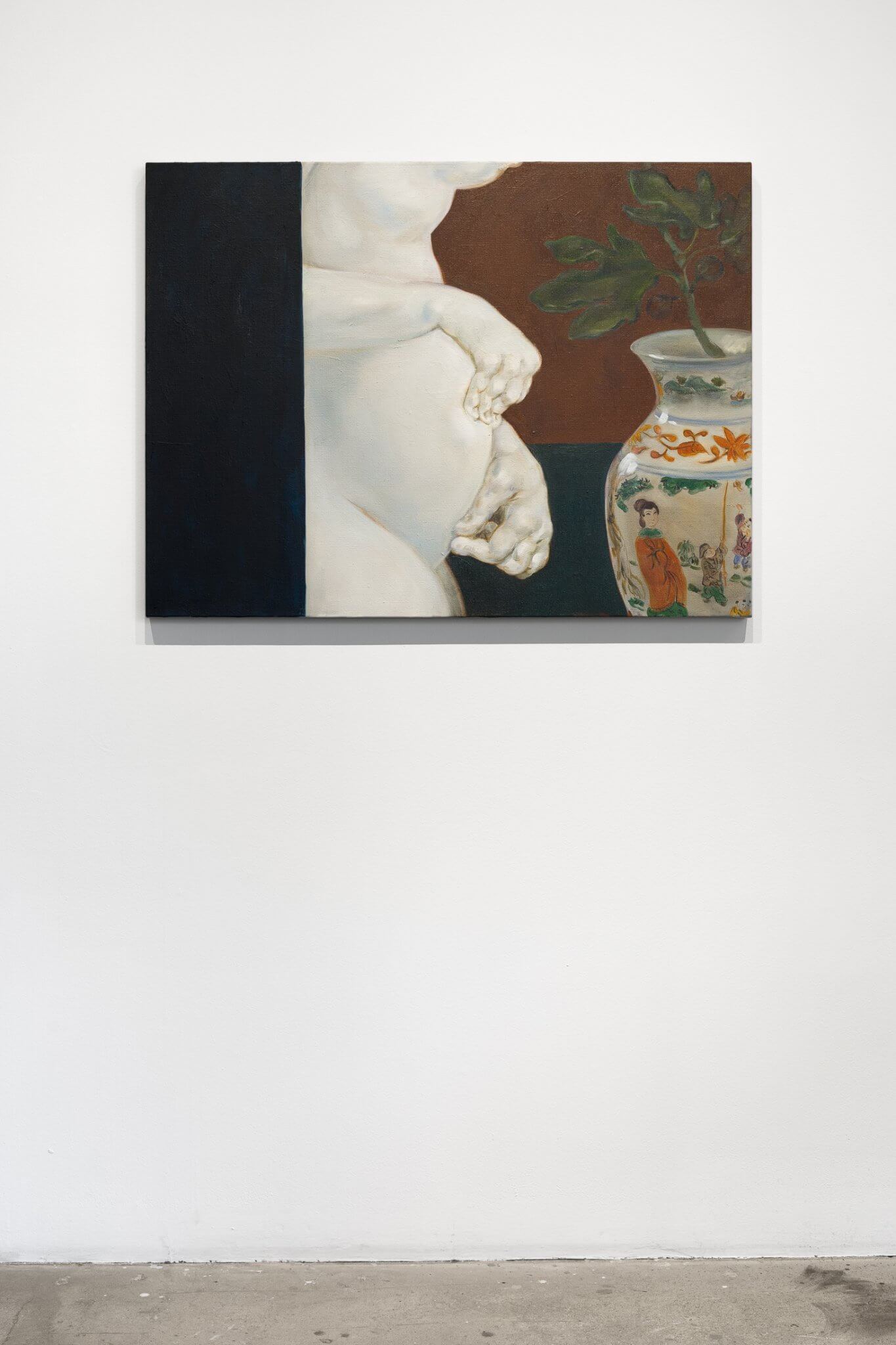

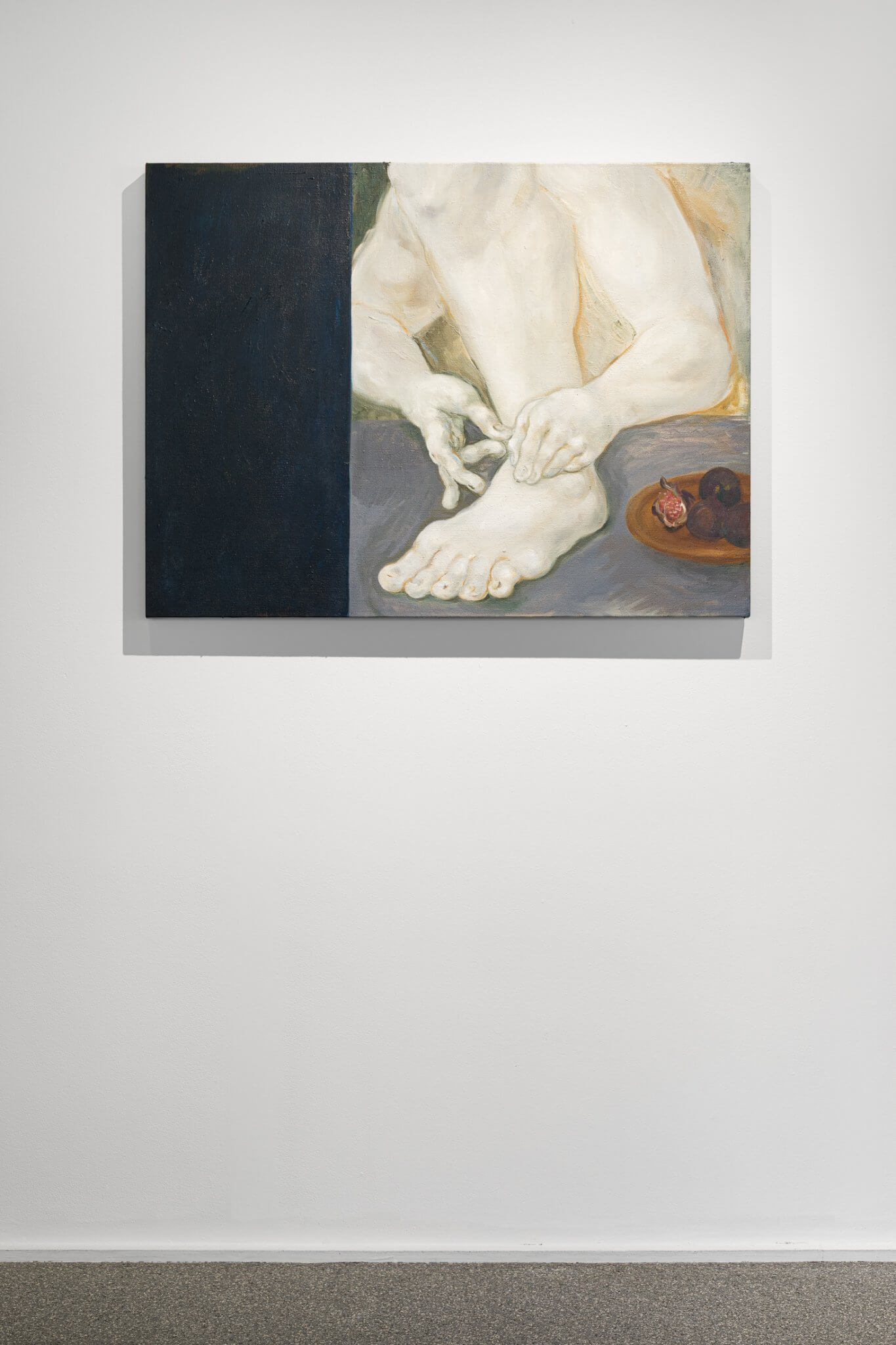

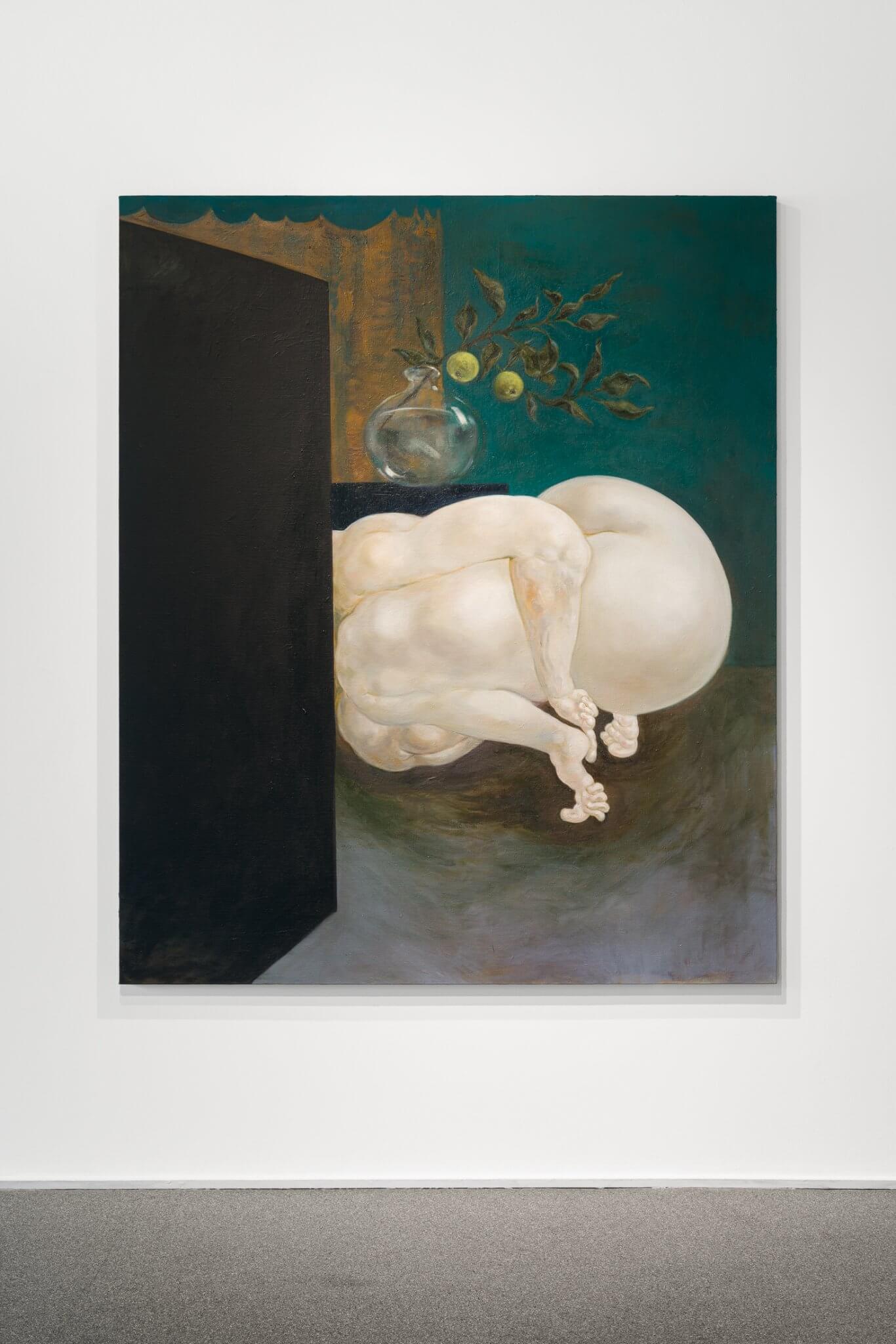

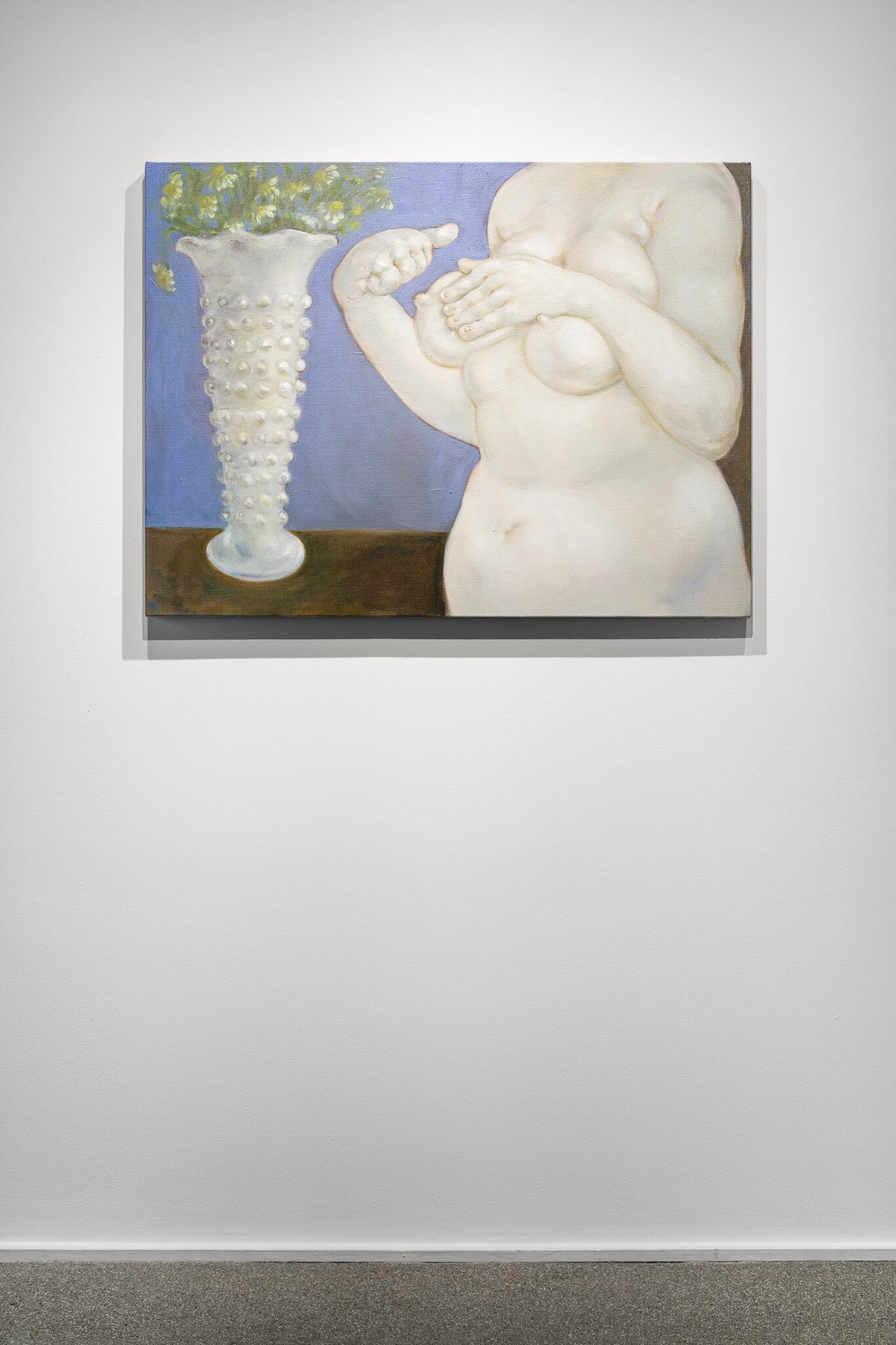

Louise Bonnet’s new paintings, all made on the occasion of the exhibition, follow the artist’s dialogue with King on gesture, embodiment, art historical sources ranging from Hans Holbein to Robert Crumb, as well as tells—the unconscious bodily movements that reveal concealed intent, such as in a game of poker. Two large-scale paintings depict nude figures in interior spaces enacting hyperbolized movements with their bodies and hands as if transposing or acting upon specific artifacts. Bonnet’s references include Ferdinand Hodler’s Auszug der Jenenser Studenten in den Freiheitskrieg 1813 (1908–09), a monumental, horizontally composed painting in the fresco tradition. In it, young soldiers perform dramatized gestures as they ready themselves for battle against Napoleon: mounting a horse, tying a backpack, and putting on a coat. Bonnet also draws on British Special Operations Executive’s 1940s manuals, which outlined tactics for Allied soldiers to pass as locals in Nazi-occupied territories. These guides covered not only forged identity papers and clothing produced with local threads and weaving techniques, but also the adoption of culturally specific gestures. In Bonnet’s paintings, the gestures remain, yet the objects they interact with are ambiguously absent.

The second floor features additional paintings by Bonnet, each capturing a detail of a motion, as if in a film still. King, too, considers her sculptures in a similar way—when arranged in perfect poses, they function as stills, highlighting their inherent capacity for movement. King’s A Pocket Anatomy (2001) presents three stands supporting disembodied fragments such as a strand of hair, an eye, and an ear, while How to make a thumb (2008) displays a sequence of ten boxwood segments in various stages of becoming components of a finger. Nearby, a vitrine housing studio objects bespeaks King’s meticulous process of making in search of a figure that seems sentient.

Across generational and mediatic differences, Bonnet and King’s works share a cinematic sense of temporality, evoking both past and future through gesture and pose to convey the potential for motion and emotion. Their interrogation of delineations between agency and passivity relates to gendered and other social hierarchies, as explored in Iris Marion Young’s essay, Throwing Like a Girl (1980). In it, the philosopher argues that perceived limitations on feminine mobility are not rooted in physiology but in societal and psychological conditioning. The political subjugation and suspension of othered bodies between life and death, extensions of biopower, and advancements in biotechnology and artificial intelligence today throw life’s definitions and valuations into high relief. Through the original pairing of Bonnet and King’s work, De Anima examines life and its semblance at this moment of heightened pressure on epistemic, existential, and technological questions of animacy.

De Anima is curated by Stefanie Hessler, Director of Swiss Institute.

The exhibition is presented with the support of Gagosian. Watchmaking Art Partner: Jaquet Droz.

Louise Bonnet (b. 1970, Geneva) lives and works in Los Angeles. Her work is in the permanent collections of the Moderna Museet, Stockholm; Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; MAMCO, Geneva; Museum Brandhorst, Munich; and Long Museum, Shanghai, among numerous others. Her work has been subject of a solo exhibition at the Hollyhock House, and was included in the 59th Venice Biennale, The Milk of Dreams; as well as in group exhibitions at The Warehouse, Dallas; Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth; Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, Turin; Aïshti Foundation, Beirut, among others.

Elizabeth King (b. 1950, Ann Arbor) lives and works in Richmond. Her work is in the permanent collections of the Hirshhorn Museum, Washington D.C.; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond; and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, among others. Awards for her work include Anonymous Was a Woman, American Academy of Arts and Letters, Guggenheim Fellowship, and Mary Ingraham Bunting Institute (now the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University). She was inducted as a member of the National Academy of Design in November 2017. She is the co-author (with W. David Todd) of Miracles and Machines: A Sixteenth-Century Automaton and Its Legend (Getty Publications, 2023). Her work has been the subject of a solo exhibition at MASS MoCA, among others; and group exhibitions at Vitra Design Museum, Weil am Rhein; Flag Art Foundation, New York; Museum of Contemporary Art, Taipei; and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, among others.

Image: Elizabeth King and Richard Kizu-Blair, What Happened, 1991. Courtesy of the artist.

Video by Nate Reininga.

Press

- Louise Bonnet and Elizabeth King: De Anima | Cultured

- Louise Bonnet and Elizabeth King: De Anima | Observer

- Louise Bonnet and Elizabeth King: De Anima | Art in America

- Louise Bonnet and Elizabeth King: De Anima | Impulse

- Louise Bonnet and Elizabeth King: De Anima | BOMB

- Louise Bonnet and Elizabeth King: De Anima | New York Times