Lee “Scratch” Perry: MIRROR MASTER FUTURES YARD | Kaleidoscope

Oct 16 2020

WORDS: FRANCESCA GAVIN

What does genius look like? The clear eccentricity of Lee Scratch Perry surely evokes it. Speaking in rhythmic, rhyming nonsense, dressed like a traveling magician-slash-holy man, he could easily come across as the proverbial madman. He is, however, arguably the most important music producer and innovator Jamaica ever produced. Between 1969 and 1978, he released almost 600 singles and 50 albums. It is not hyperbole to say that without Perry, there would not have been Bob Marley, hip hop, or electronic music as we know it today. By accident or intention, he changed the face of modern sound.

Rainford Hugh Perry was born 1936 in Kendal, Jamaica. He grew up in the countryside of the island, the third of four children. After a tough and very poor childhood, he started working as a tractor driver, helping to build the first road in Negril, emerging in response to the rise of tourism in the mid-1950s. Perry later said this was the formative sonic impetus of his life. “I was working with rock and hearing the sonic vibrations. I’m sure that’s where everything comes from,” Perry explains on the 2008 documentary The Upsetter. “I learnt everything from stone.” In 1961, he left for Kingston, the heart of the country’s music scene. In 1962, Jamaica declared independence from UK, and a sense of new freedom pervaded the island. At that point, ska was the native sound, booming with mobile sound systems. Perry worked at all the local studios—initially as a handy man, before working his way up to producing and writing tracks. After garnering the name “Scratch” for an early release, his breakthrough song was “People Funny Boy” in 1968. An insult to his exploitative former boss Joe Gibbs, the track was inspired by the sound and sense of spirituality Perry had experienced at Kendal Baptist Church. It opens with the sound of a baby crying—the first sample ever used in recorded music. It featured some of Perry’s signature traits: a syncopated beat, reflecting traditional African Burru and Kumina drum styles; a strong electric bass; and guitars used not just for melody, but as a rhythmic element. It was one of the first songs that moved rocksteady into reggae. The single sold 60,000 copies and established Perry as a successful recording artist.

It was the following year that Perry got his second nickname. In “I am the Upsetter,” Perry sings, “I am the avenger, you’ll never get away from me / I am the Upsetter.” His vengeful lyrics are a fascinating contrast to an almost upbeat melody. Perry was making a statement, however, as someone revolutionary and radical, not afraid to upset perceptions and transform experience. On the back of the song’s massive popularity, he set up a label and group called The Upsetters. In 1970, Bob Marley joined the label’s record shop on Charles Street and began to collaborate with the producer. They had known each other since the early days at Studio One; the singer had minor success with The Wailers, but that was waning. Together, they invented a new sound that would transform Marley’s career. Marley had moved in with Perry while they recorded the singles “Soul Rebel” (1970), “Duppy Conqueror” (1971) and “Sun is Shining” (1971)—arguably Marley’s best works. The sound was spacious, layered, and fresh. As Perry later recalled, “I was playing the part of the prophet, and Bob was playing the part of the king to establish the music.” The magical combination fell apart but nonetheless, it did introduce Marley and reggae itself to an international audience. Marley and Perry’s collaborations also addressed the socio-political experience of contemporary Jamaican life—something innovative at the time. Marcus Garvey’s rhetoric in particular had a huge impact on Jamaica during Perry’s life. Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) was founded in 1914 in his native Jamaica and established in Harlem in 1916, where he had moved from Kingston. Reflecting a desire to unite and lift the African diaspora “New World,” Garvey glorified African civilization and Black superiority, and even began practical projects for repatriation to the continent. Although a controversial figure who believed in Black separatism and had even collaborated with the KKK, Garvey still had a huge image. He looked to Black Christian churches that saw Ethiopia as the biblical center of the world; Ethiopia in turn embraced this allegorical image of spiritual fulfillment, “Zion.” Garvey had reportedly said, “Look to Africa for the crowning of a Black King; he shall be the Redeemer.” Haile Selassie was crowned as King of Ethiopia in 1930, seen by many in Jamaica as a living god whose bloodline was supposed to link to King Solomon. Rastafarianism was born. Perry was a true believer, and was among the crowds that greeted Selassie on his visit to Jamaica in 1966. Many of his lyrics and references draw from his religious beliefs.

Dub was not just a new kind of sound or genre—it was an entirely new methodology. As Erik Davis has written, “dub is not only a musical style, but also an artistic discourse, in the aesthetic act of making dub—a type of remixing that emphasizes the phatic effects of sonic space.” The studio became an instrument. Perry pioneered the use of phasers and drum machines, patching together sound with scratches, feedback, and distortion. The tracks were layered with echo, reverb, guitars, and samples, with voices hovering in space above the backing tracks. The multiple layers of rhythm echoed the polyrhytmic approach of West African religious drumming. Perry’s work fused ideas around identity, history, and religion, reflecting the complexities of the Afrodiasporic experience. His 1972 instrumental album Cloak & Dagger was adopted by a younger generation of Jamaicans, attracted to its abrasive instrumentals and then-radical techniques. It became a template for his later approach: a mix of slow beats, layered of sound and chaotic lyrics. In 1974, Perry opened his own studio, The Black Ark, at 5 Cardiff Crescent in Kingston. With circuitry designed by King Tubby, the space cost a fortune. It was equipped with a four-track sound board, an Echoplex delay unit, a Roland space echo, and a Teac recorder. It also allowed Perry to work constantly without having to rent the space. Having the studio on-site also meant Perry could constantly experiment. He would record his children’s toys and TV dialogue, bury recordings in the garden to get more feedback. He was constantly building rhythms and extending ideas, often with a fluid session crew. It anyone came with an idea to start a track, he already had something to expand on. He was insanely prolific during this period, creating 400 singles and numerous albums for hundreds of artists. “The Black Ark was a school,” explained singer Junior Delgado. “Scratch trained you. You had to know music inside out—not just the singing, but the chords, the chord changes, the rhythm patterns. Everything.”

From the start, Perry saw the Ark as a religious space. “I see myself rebuilding the temple of King Solomon,” he said. It was named after the Ark of the Covenant carried by the tribes of Israel to Canaan, the promised land of Rastafarianism. The studio was covered in art and graffiti, a portrait of Haile Selassie above the entrance. Dreadlocks moved in to the space en masse, and vast quantities of white rum and ganja were consumed; more than hedonism, however, the focus was on peace, love, and a positive shift. The mid-1970s was a period of economic distress, gang violence, and social upheaval for Jamaica: cocaine encouraged by South American cartels was flooding the country; Americans in their “war on drugs” were arming the opposition; there was a high level of police corruption. Perry was not afraid to address this in the music he was making, like “War Inna Babylon” and “Chase the Devil” by Max Romeo and Junior Murvin’s iconic “Police and Thieves.”

At the same time, Perry also provided his own take on Afro-sci-fi narratives. He presented an image of a producer fused with the machine. “By giving flight to the producer’s cybernetic imagination, dub created room within the Afrodiasporic culture for a cyborg mythology grounded in technical practise,” Erik Davis writes in Sound Unbound (2008). Science-fiction imagery had appeared on Perry’s record covers; Perry himself has been keen to highlight the man-machine interface. “The studio must be like a living thing,” he explained in characteristic terms. “The machine must be alive and intelligent. Then I put my mind into the machine by sending it through the controls and the knobs or into the jack panel.” Kodwo Eshun nods to John Corbett’s essay “Brothers from Another Planet” in writing that Perry, along with Sun Ra and Parliament, “work[ed] with a shared set of mythological images and icons such as space iconography, the idea of extra-terrestriality, and the idea of space exploration.” The Black Ark was a musical spaceship straight out of Perry’s imagination, one that tapped into a techno-visionary tradition balancing African history and belief with future possibility.

From the start, there was a strong relationship between Perry—and in fact the entire Jamaican music scene—and the UK. The windrush arrival of Jamaican and other West Indian immigrants rebuilding the country after the war also brought huge musical influences. British Mods and skinheads had embraced ska as their sound; Perry, like fellow producers Joe Gibbs, Bunny Lee, Harry J, and Derrick Harriot, had at least one English label from his early days. Working-class British mods growing up in the same parts of South and West London as West Indian immigrants listened to the same music, adopted West Indian style, and were attracted to the secret, underground clubs and house parties in the scene. Perry’s music was among the reggae, rocksteady, and ska that became the soundtrack to the skinhead scene.

British bands in particular started looking to reggae producers to invigorate their sound. The Clash invited Perry to London to work on their second album in 1976. Eager to escape Jamaica’s violent scene, Perry agreed. Having long idolized Perry and his work, the band covered “Police and Thieves,” shifting the reggae of the original recording into a different sound. Perry worked on making their heroin-fueled chaos palatable; however, like the blues musicians who had credited British rock bands for keeping an interest in their music alive, collaborations like this gave Perry relevance. “I am a punk,” Perry proclaimed. “Anything I want to do, I do it. Punk is magic.” Rock acts from Britain and America were booking themselves into Jamaican studios: Paul and Linda McCartney, Robert Palmer, and Johnny Rotten all collaborated with Lee, who also reconnected with Bob Marley during the 1977 trip, recording together once again. Things began to unravel towards the end of the decade. In 1977, at the Black Ark, Scratch recorded The Congos’ album Heart of the Congos, an album which has been described as possibly the best reggae album ever made. Perry was using the three vocalists’ voices as instruments with great success; Perry’s London label, however, balked at the spiritual content and refused to release it. His relationship with the band ended. In 1979, his wife left him with their children. He was increasingly being harassed and extorted for money. People began to think Perry had lost his mind, as he was walking backwards and covering the studio with minute written nonsense and striking the ground with a hammer. Perry felt jinxed. Finally, in 1983, the studio burned down, marking the end of the reggae era.

In the 1980s, Perry entered a decade of alcohol and depression. His legacy and career, however, did not end. At the end of the decade, he met his Swiss wife Mireille, a former dominatrix and reggae record shop owner, and the pair moved to the mountains outside of Zurich. He became vegetarian, gave up ganja and alcohol, and saw a shift in his career. In his 50s, he returned as a solo artist. In 1998, he appeared on the Beastie Boys track “Dr. Lee, PhD” from Hello Nasty, an album which sold over 1 million records. He was awarded a Grammy for Best Reggae Album for the 2003 record Jamaican ET. Increasingly, he was repositioned as a vital cultural pioneer. Jamaican-American DJ Kool Herc, who helped give birth to hip-hop in the Bronx, has noted the influence of Perry’s records in the early days of MCs.

British dance culture was also heavily inspired by his take on dub. The Prodigy sampled him on the iconic pop-rave track “Out of Space” in 1992. Underground scenes like ragga, jungle, dancehall, and later drum’n’bass took dub space and method and adapted it for a new concept of sound system culture. Bass, dubstep, and grime took things a step further. None of these genres would have existed as we know them, without Perry’s impact on Afrodiasporic music culture.

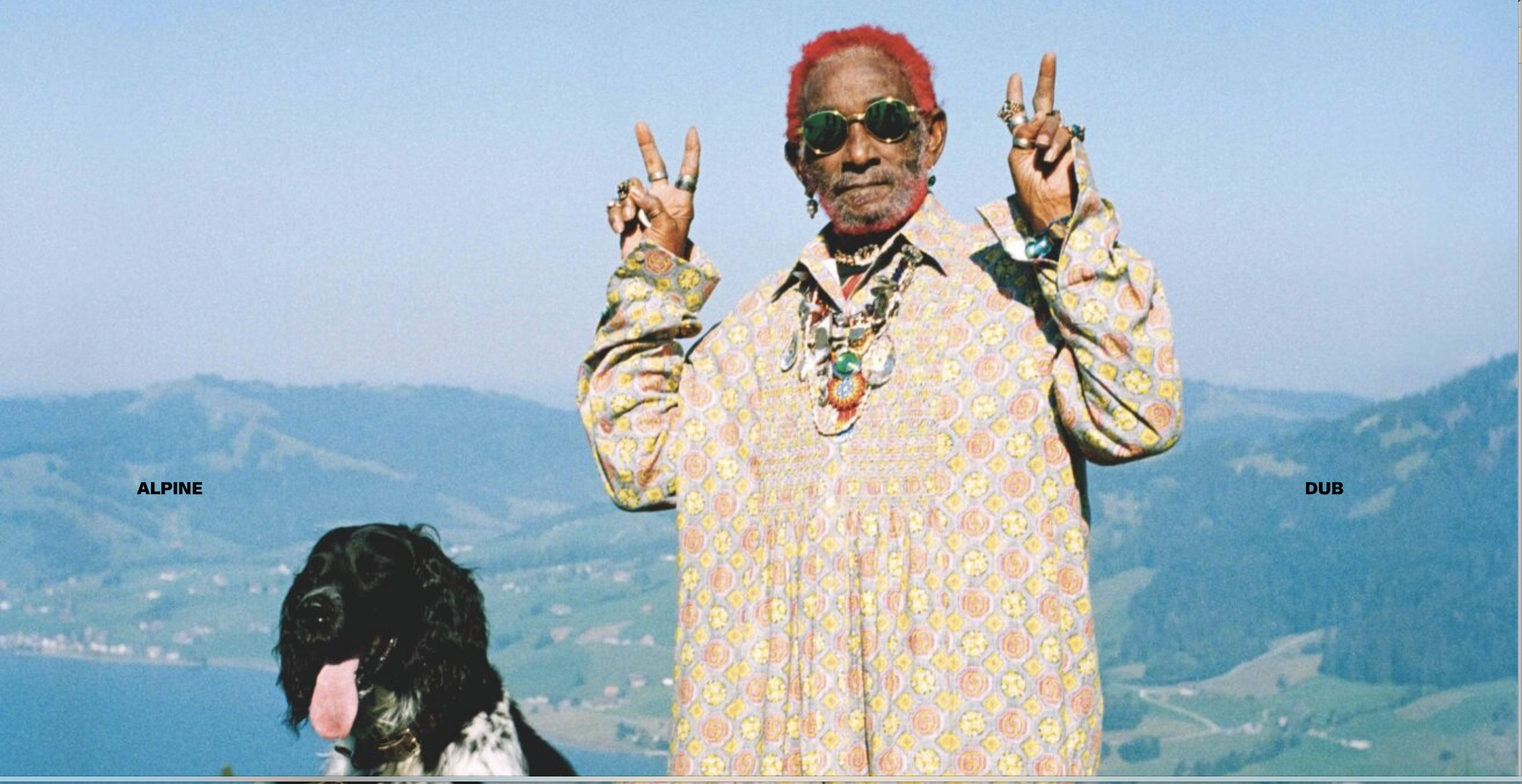

In recent years, Perry has also been embraced by the art world. In June 2019, he had a solo show, “Mirror Master Futures Yard” curated with Lorenzo Bernet, at New York’s Swiss Institute (later moving to Corbett-vs-Dempsey in Chicago). The show included works made at Black Ark, gathered from Jamaica in the late 1990s, and from his Blue Ark studio in Einsiedeln, Switzerland. Perry’s work is a melange of media and method, his floor, totemic, and wall pieces composed of a plethora of materials: old CDs and art postcards, scrawled texts and lyrics, mirrors, a TV screen surrounded by a pile of stones, images of the Swiss Alps, flags with Haile Selassie and Jah printed them, sticks, pieces of ginger, old defunct recording equipment, Black Madonna figurines, toy monkeys, defunct laptops, cordless phones, paintbrushes, lion statues, and at the heart of it, rocks—still Perry’s founding material. “I like to do things with rocks. Rocks have been used by mankind forever. Back in the Stone Age, rocks were used for tools. The minerals and metals in rocks have been essential to humans. You can get crystals and granite from them. Nothing stops me in life because I stand on a foundation solid as a rock.” Perry has said painting and art itself has “turned me into a super being.” His costumes and clothes have the same aesthetic: like some medieval holy man, he dresses in hats and outfits covered with pendants, bits of tape, buttons, old machinery, and patches. Again, everything has numerous pan-African, Rastafarian, and Christian references, including lions and crosses. There is a strong connection to his music-making, too, as imagery and objects are perpetually remade and remixed.

Perry is now in his 80s, but his legacy persists. As Michael Veal writes of Perry and his fellow producers in Dub: Soundscapes & Shattered Songs in Jamaican Reggae, “They created a music as roughly textured as the physical reality of the place, but with the power to transport their listeners to dancefloor nirvana as well as far reaches of the cultural and political imagination: Africa, outer space, inner space, nature, and political/economic liberation.” As Perry himself has stated, “I’m telling you about the power of the Black Man Sound, Words and Power conquer all.” We’re listening.