Hans Schärer | The Huffington Post

Dec 04 2015

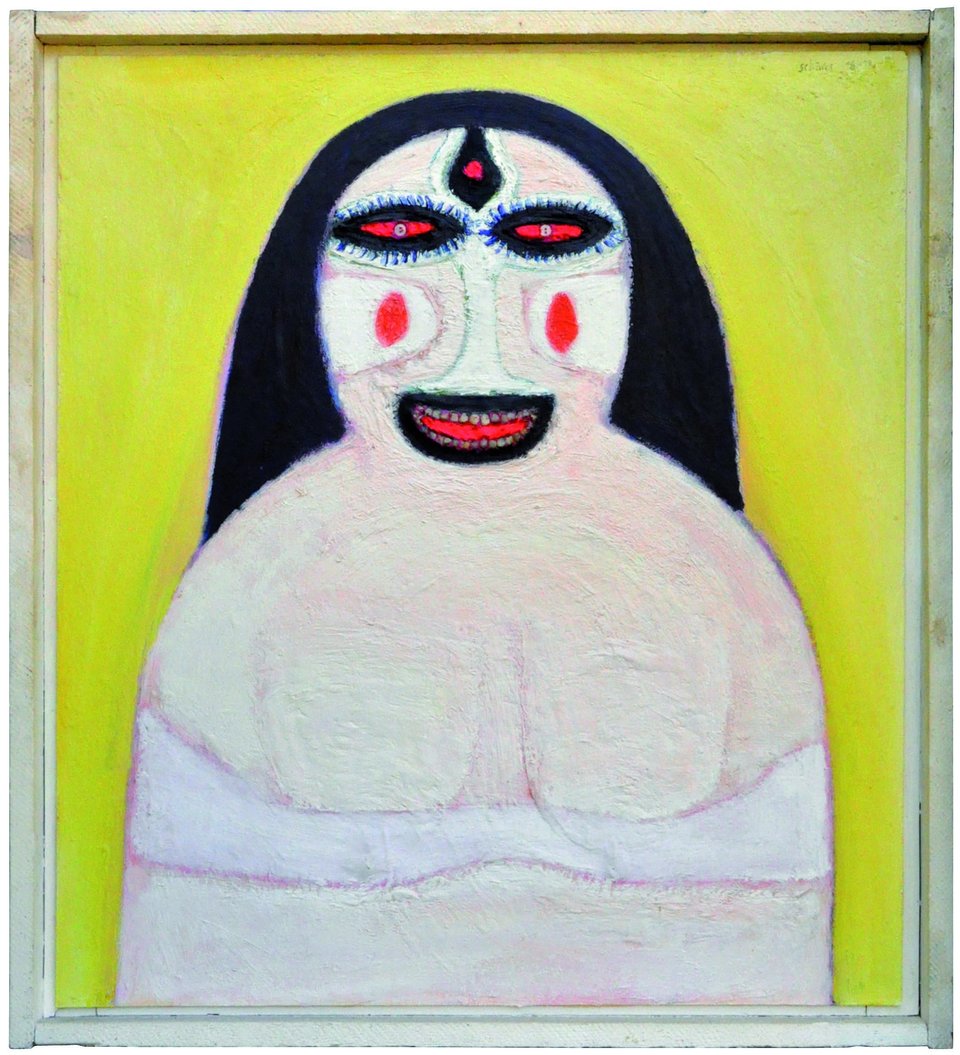

Throughout the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s, self-taught artist Hans Schärer painted over 100 women — he dubbed them Madonnas — following a single, strict formula. He’d create an egg-shaped head and plop it atop an ovalesque body with no neck in between, forming the silhouette of a Russian doll cropped at the bust. The facial features he painted hover somewhere between a Byzantine portrait and a voodoo doll. His women look more like the Babadook than the typical mother of god.

Each of Schärer’s Madonnas is unique in its particulars — one grins, one grimaces, one rests agape, all equally unsettling. Some are the colors of ghosts, others are draped in rainbows. Most don cloaks and boast long, clumpy hair. The Madonnas are made from oil paints layered on thick, with occasional stones, hairs and keys tangled up in the layers of pigment.

Schärer was born in Switzerland and moved to Paris in his 20s to become an artist. Art Brut was in vogue at the time, which made his lack of training all the more appealing. He achieved moderate success in his time — he died in 1997 — though his legacy never extended far outside Switzerland. The Swiss Institute is currently hosting his first solo exhibition in the United States, titled “Madonnas” and “Erotic Watercolors.”

The Madonnas are stark, static representations of female totems, utterly fearsome and slightly erotic — notice the repetition of vulva-like shapes on their bodies and faces. The watercolors, then, are almost the opposite, a cacophonous jamboree of erotic and powerful femininity played out in nasty and fabulous scenarios. They’ve garnered the attention of people like artist Cindy Sherman, who included the army of feminine idols in her exhibition at the 2013 Venice Biennale. It makes sense; the Madonnas physically resemble masks, uniform yet distinct, while Sherman’s photography plays off the various masks women wear. All self-portraits, they too are variations on a single motif.

In Schärer’s image above, five nude women — actually, one is wearing black stockings — ride down a snowy mountain slope on a penis-shaped, checkered toboggan. The nearly identical riders laugh in unison, their tongues dangling in the breeze like generously sized fruit roll-ups, nipples pointy from the cold.

The women, contrary to the bone-chilling Madonnas above, are sexual without being sexualized. Dominant, playful, lewd, hungry and potentially dangerous, they are subordinate to none, free to frolic in their own garden of otherworldly delights. Somewhere between the work of 19th-century outsider artist Aloise Corbaz, where sensuous women tower over the occasional puny male, and Tomi Ungerer’s ecstatically sex-positive illustrations, Schärer’s watercolors conjure erotic playgrounds full of big boobs, big butts, big teeth and big appetites.

Schärer’s work, at least as evidenced by these two major series, breaks down binaries of all shapes and sizes. His oeuvre’s obsessive repetition and naive style would point to an “outsider” distinction, as would his status as a self-taught artist. However, the fact that this style was likely due at least in part to an insider knowledge of contemporary art world’s latest trends, places his somewhere in between.

Likewise, his visual representations toy with the Freudian characterizations of the Madonna and the whore while chewing away at them from the inside. The Madonnas, despite their rigid exteriors and haunting expressions, still emit a certain sexuality, even if it’s a fear-inducing breed. His erotic watercolors, too, while sexual and crass and lots of fun, radiate a sort of spirituality. Think Dorothy Iannone’s concept of ecstatic unity, a transcendent state reached through sexual rapture.

Whether a spiritual matriarch or a Dionysian Amazon, the women of Schärer’s painted world offer a glimpse into a particularly and wonderfully tangled male perception of femininity. It’s a hell of a lot more intriguing than the typical male gaze.

“Madonnas” and “Erotic Watercolors” will be on view until Feb. 7, 2015 at the Swiss Institute of Contemporary Art in New York.